Under the scorching Bangladeshi sun, a group of Rohingya women trekked the steep slopes of Cox’s Bazar district singing a plaintive song:

Rape can happen to anyone.

I am not happy for this rape.

Nobody is here to listen to me.

Rape is not my fault.

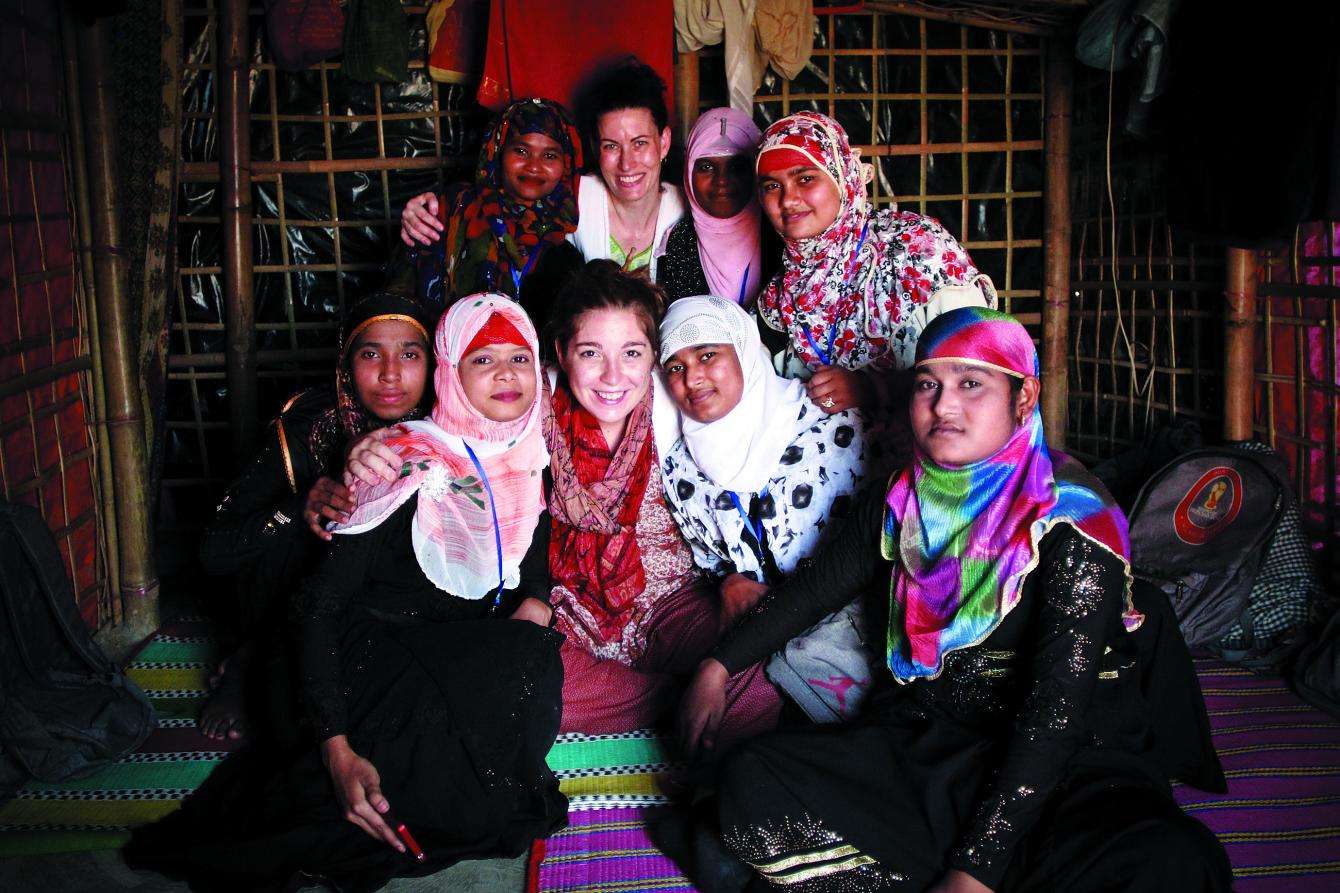

These young volunteers are part of an MSF outreach team for sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). They spend their days going door to door across the massive Rohingya refugee settlements in southern Bangladesh, gathering small groups of women to talk about sexual violence and the care available for survivors.

“After rape, come within three days for medicine,” sing the volunteers. “MSF offers free treatment and is also confidential.” They tell women that when they come to the clinic, they can point to a printed symbol or use code words for rape to avoid stigma or unwanted attention.

The Rohingya are a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority who have lived in Myanmar for hundreds of years and have endured persistent discrimination and abuse. Following a massive campaign of targeted violence against the community that began on August 25, 2017, more than 693,000 Rohingya refugees fled across the border to Bangladesh. They joined thousands of other Rohingya refugees already living in Bangladesh in squalid makeshift settlements after earlier cycles of violence and mass displacement.

Health surveys conducted by MSF teams in Balukhali and Kutupalong makeshift settlements—the two largest settlements in Cox’s Bazar—indicate that at least 6,700 people, 730 of whom were under the age of five, were killed within the first month of “clearance operations” launched by Myanmar security forces. Our patients have described widespread violence, including sexual violence.

The challenge with treating these particular women and girls was how brutal their experiences had been.

“The challenge with treating these particular women and girls was how brutal their experiences had been,” said Aerlyn Pfeil, a midwife and MSF-USA board member who helped expand the program in Cox’s Bazar to treat survivors of sexual violence last October. “A lot of gang rape, a lot of public rape, some girls who were taken for days and assaulted, often [repeatedly].”

Rashida, a 25-year old Rohingya woman, cried as she recalled the day her village was attacked by soldiers. “They made us stand all night, until dawn,” she said. Rashida tried to escape along with a group of women, but they were recaptured by the soldiers. “They killed my beloved son right in front of me. Then they closed the door and dishonored me…. [They] started slashing our bodies with knives.” Rashida survived by laying still among the bodies.

Even before the latest crisis, Rohingya women and girls were frequent targets of sexual violence in Myanmar. During the 2016 military campaign that forced tens of thousands to flee, many women sought care for sexual violence in MSF’s Kutupalong clinic in Bangladesh.

A number of them had been raped several months prior to seeking care. “[Even] before this, the military would often come and take women. Many women disappeared,” said a woman from Buthidaung township. “They raped them in the mountains or in the jungle, or took the women to their camp . . .We were always afraid.”

Once they reached the refugee settlements in Bangladesh, many Rohingya women delayed seeking care for a variety of reasons, including lack of knowledge about the medical consequences of sexual violence, cultural stigma, and all the pressures of daily survival.

“Violence is a historical reality for a lot of Rohingya women,” said Siobhan O’Malley, MSF midwife. “People don’t necessarily think that sexual violence is something you would seek care for unless there is a physical injury—or months afterward, when they discover they are pregnant.”

MSF medical care for survivors of sexual violence covers testing for and preventive treatment against sexually transmitted infections, menstrual regulation, and psychosocial care, as well as vaccinations for tetanus and hepatitis B. However, some medicines, such as emergency contraception and post-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV, must be given in the first 72 hours to be effective.

FINDING A PLACE OF PEACE

Prior to the latest emergency, MSF psychologist Cynthia Scott was working in Kutupalong camp counseling the Rohingya and in the capital, Dhaka, working with Bangladeshi survivors of sexual and intimate partner violence. Following the August influx, she stayed in Kutupalong full-time to help respond to the growing emergency.

“At the beginning, Rohingya women were not coming for sexual violence,” she said. “People were just focused on finding food, water, and shelter.”

During the early days of the emergency, Scott and her team at the Kutupalong hospital would only see the most vulnerable Rohingya women brought in—those with disabilities; those found in ditches or on the side of the road.

“One woman didn’t know who she was,” said Scott. “We could tell she had been beaten, so we just sat with her for a few days until she could speak.”

Later, patients would come in ostensibly seeking care for physical ailments such as body pains and headaches.

“That’s one of the benefits of integrating mental health programs in medical settings,” she said. “We can do psychosocial education in the waiting room.” MSF counselors, all of whom are Bangladeshi, hand out water and biscuits in the waiting room and explain common trauma symptoms. One day, two women at the clinic suddenly started crying. A counselor sat next to them and asked if they wanted to talk; both women were survivors of sexual violence.

“We call the center ‘shanti khana,’ which translates to a place of peace,” said Scott. If they notice anyone in distress, the MSF triage nurses will ask the patient if they would like to go to the place of peace, a name that helps reassure women and avoid stigma.

A TREMENDOUS VIOLENCE

The SGBV outreach team often starts the group sessions with a story about sexual abuse or assault that then leads into a conversation about the health care provided by MSF, including the safe termination of pregnancy.

“For Rohingya women pregnancy outside of marriage is not just frowned upon, it is impossible,” said Liza Ramlow, midwife supervisor at MSF’s hospital in Balukhali settlement. “It is a tremendous violence that happens to women and can have serious consequences.”

In Myanmar, the Rohingya were often denied access to public health care, so women and girls typically fend for themselves. They seek advice from traditional healers or buy medicines from the camp themselves to end an unwanted pregnancy. “We see a lot of incomplete, septic abortions,” said O’Malley, the midwife supervisor. Patients come into the clinic hemorrhaging, extremely sick, and for MSF’s midwives it’s a race against time to save their lives. “Girls take matters into their own hands because they feel that is their only option.”

MSF is responding to the additional needs of pregnant survivors of sexual violence and children born from rape. Teams are working with other organizations in Cox’s Bazar to ensure the safety of both mother and child. An MSF hotline is also available for survivors of sexual violence to receive information about how to reach our services as soon as possible.

CONFRONTING ABUSE ON ALL LEVELS

The horrific living conditions in the camp have contributed to cases of violence between intimate partners and among families and neighbors.

“Many people are on edge, not just because of the recent trauma but because of the long-time trauma of witnessing horrific things,” said Scott, the mental health supervisor.

In January, there was an increase in suicide attempts admitted to MSF’s hospital in Kutupalong. “Women came in having tried to poison themselves, and we would then discover that they are victims of domestic violence,” said Scott.

The Rohingya are denied citizenship in Myanmar and have not been officially recognized as refugees in Bangladesh, adding to the pressures. Women and children in the camps are also particularly vulnerable to exploitation, and have been targeted by human traffickers.

“One of the cruelest facts is the Rohingya have been deprived of so much,” said Ramlow, the midwife. “It’s like the water you swim in, it’s the air you breathe, it’s abuse on all levels.”

The crowded makeshift settlements are especially dangerous at nighttime. Around two-thirds of the camps’ residents are women and children, according the United Nations. They are constantly exposed to risk—with no locks on doors, no lights after dusk, and no protection when they have to go into the forest alone to collect firewood. Many patients say they have difficulty sleeping, paralyzed by the fear that someone might come into their homes, haunted by memories of the attacks by Myanmar security forces.

MSF’s Balukhali hospital runs a 24-hour volunteer ambulance service made up primarily of Rohingya men living in the camps and trained to identify refugees who need urgent care. At all hours of the night, they can be seen crossing the hilly landscape carrying women in blanket slings tied to bamboo poles. “No one would come at nighttime if we didn’t have these volunteers to accompany them,” said Ramlow.

The road to recovery is long and hard for survivors of sexual violence. But Roksana, a Bangladeshi midwife who has been working in Kutupalong for six years, marvels at the extraordinary resilience of her patients. She shared the story of a woman who was gang-raped during the recent violence in Myanmar, beaten, and left unconscious. This woman then managed to walk for more than 15 days to cross the border and make her way to the settlements.

“Even after this, she had the perseverance to come to Bangladesh and survive,” said Roksana, fighting back tears. “Mentally she is still strong. She deserves our respect.”