Premature birth is the leading cause of death for children under 5 years old. It’s also quite common across the world—but the chance of survival depends on where a child was born.

In low-income countries, an estimated half of all children born preterm will die, while nearly all would survive if they were born in a high-income country like the United States or Canada, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Most of these deaths can be prevented with access to basic medical services during and after pregnancy—yet this care that is inaccessible in some communities, including many of the places where Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams work, like Central African Republic (CAR) and Nigeria. In these countries the mortality rates related to prematurity are 17 and 7 times higher than in Western Europe, respectively. In CAR and Nigeria our teams support the ministries of health in improving preventative and curative services linked to prematurity—and around the world we provide prenatal care, birth assistance, and postnatal care wherever the needs are greatest.

The facts about prematurity

Prematurity, or preterm birth, refers to children born alive before 37 complete weeks of pregnancy instead of the full pregnancy duration of 40 weeks. Prematurity can be categorized as ‘extremely preterm’ (before 28 weeks), ‘very preterm’ (28 to less than 32 weeks), or ‘moderate to late’ preterm (32 to 37 weeks).

Why is prematurity a concern worldwide?

There is still much research to be done to determine the causes and mechanisms that explain prematurity, including genetic factors. Research shows that some chronic conditions can be conducive to premature birth, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, infections (including some STDs), certain anomalies of the reproductive organs, having multiple pregnancies in a short period of time, delivering at a young age, and being pregnant with twins, triplets, or more. Other factors that could play a role in prematurity are smoking, drinking alcohol, using drugs, and even the effects of extreme heat. In addition, some pregnancy complications or infections require early induction of labor or a cesarean birth.

Where is prematurity most common?

The vast majority of preterm births occur in two regions: southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In 2020, 45 percent of all preterm births occurred in just five countries: India, Pakistan, Nigeria, China, and Ethiopia.

The same year, an estimated 1.2 million preterm newborns were born in 10 of the most fragile countries affected by humanitarian crises: Afghanistan, Chad, CAR, Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. In these areas, access to preventative and curative care for preterm babies can be extremely challenging.

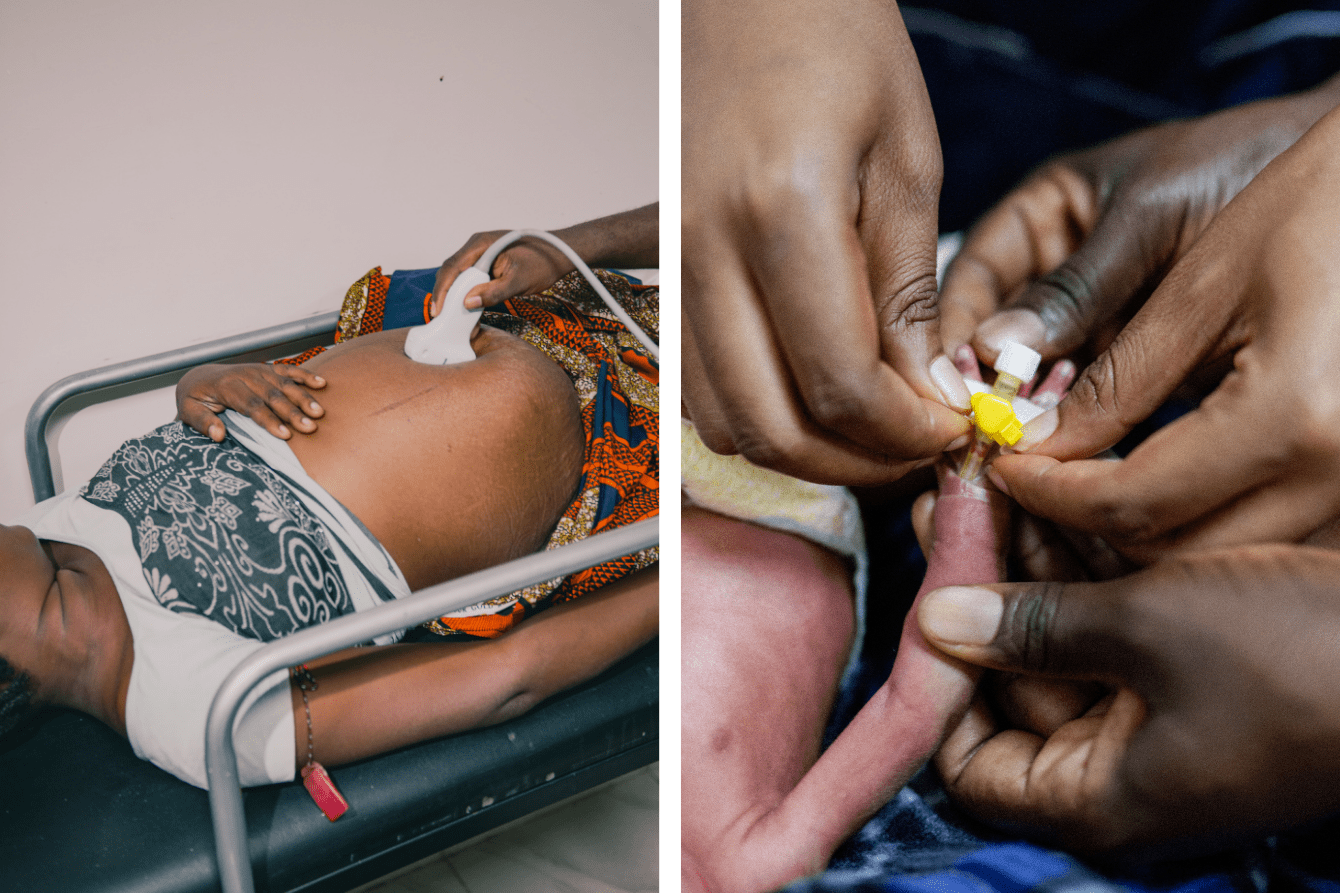

Nigeria 2024 © Colin Delfosse

The impact of premature birth on children

Early birth can pose serious health risks to a newborn baby as many organs are still growing and developing in the final weeks of pregnancy. Babies born preterm may face more direct health problems and often need to stay in the hospital longer, including in newborn intensive care units (NICUs). The earlier a baby is born, the more likely they are to have health problems. Premature babies may also be at risk of developing long-term consequences such as neurodevelopmental delays, vision and/or hearing impairment, chronic respiratory issues, behavioral and psychological effects, and growth and developmental delays.

Finding and treating health problems as early as possible—and preventing preterm birth when possible—can help babies lead longer, healthier lives. This calls for regular prenatal consultations to help identify risk factors and take action, as well as improving medical care during labor and birth, and adapted care for preterm babies. This is where the gap between high income and lower income countries is most striking.

How MSF is helping premature babies

In CAR, where the mortality rate related to prematurity is 17 times higher than in Western Europe, MSF inaugurated a comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care unit in 2022 in Bangui’s Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Communautaire. This MSF-supported 43-bed unit is the only facility in the capital providing free emergency obstetric and neonatal care.

In Nigeria, where the mortality rate related to prematurity is 7 times higher than in Western Europe, MSF teams provide support for a network of maternity units in Maiduguri and completed the construction of a hospital entirely dedicated to these services in June this year. This referral facility has been integrated into the public health system, with MSF teams training Ministry of Health personnel on patient care, including care for premature infants.

In both projects, MSF teams are using and teaching the “kangaroo care” method, an efficient method in which premature babies are held close to their mother’s bodies up to 24 hours a day, with exclusive breastfeeding. The prolonged skin-to-skin contact keeps them warm, provides constant connection, and ultimately reduces newborn illnesses while improving their chances of survival.