Many Sudanese refugees who have sought safety in eastern Chad after fleeing the conflict in Sudan are surviving in dire conditions, with only limited access to clean water, sanitation, and health care facilities.

In interviews with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams in eastern Chad, refugees describe their current situation in camps as “hell” and “humiliating.” Many have experienced violence during their journey in search of safety, including sexual violence, targeted ethnic violence, and the loss of relatives. This trauma amplifies the sense of hopelessness for many stranded in the camps.

Chad hosts more than 708,000 Sudanese refugees and returnees who have fled the war in Sudan since April 2023. MSF teams in Chad are providing refugees with medical care, including surgery and malnutrition treatment, as well as water and sanitation support and relief items like plastic sheeting, soap, and mosquito nets. However, the needs remain dire, particularly as the rainy season raises the risk of waterborne diseases and other health issues.

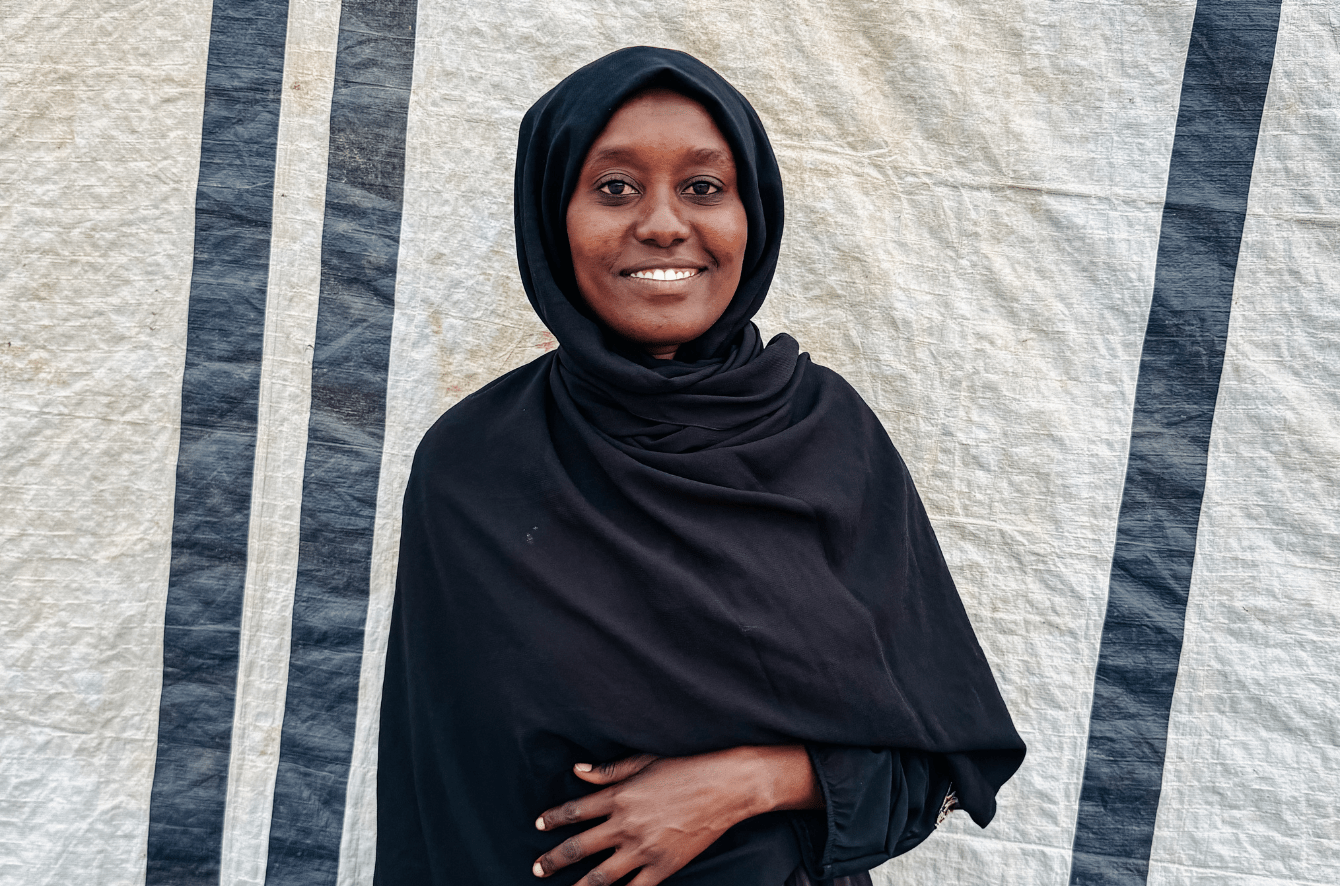

"Stuck between an uncertain future and a place I don’t belong"

My family is incomplete here. There are nine of us in total—my mom, my dad, and seven of us siblings—but the war separated us. Some of my family made it out of West Darfur, but the rest haven’t joined us yet.

We fled in a state of panic, terrified of the war. We didn’t have time to take anything with us, and some of us even arrived barefoot. We walked 12 miles to get here, on foot. Along the way, we encountered Rapid Support Forces who threatened us. Some of the young men traveling with us were accused of belonging to the Masalit tribe [a minority group that faces targeted violence]. They were arrested and killed. We thought we would die too. I couldn’t imagine we’d survive.

The memories of fleeing stay with me. When I think about the tragedies, what pain we left behind, there’s no way I can go back.But I hear some people say they would rather return to the war in Sudan than endure the hell we face in the camp.

I got here in July of last year, and I’m 24 years old now. Our situation is tragic. We left one difficult situation, only to find ourselves in an even worse one. We lack the basic necessities for living. It’s been four or five months in Iridimi camp since we last received any food aid.

Now, my family and I are desperate. We need education, health care, and a better future. But the reality we live in is bleak. I feel stuck, caught between Sudan, where the future is uncertain, and Chad, where I don’t belong.

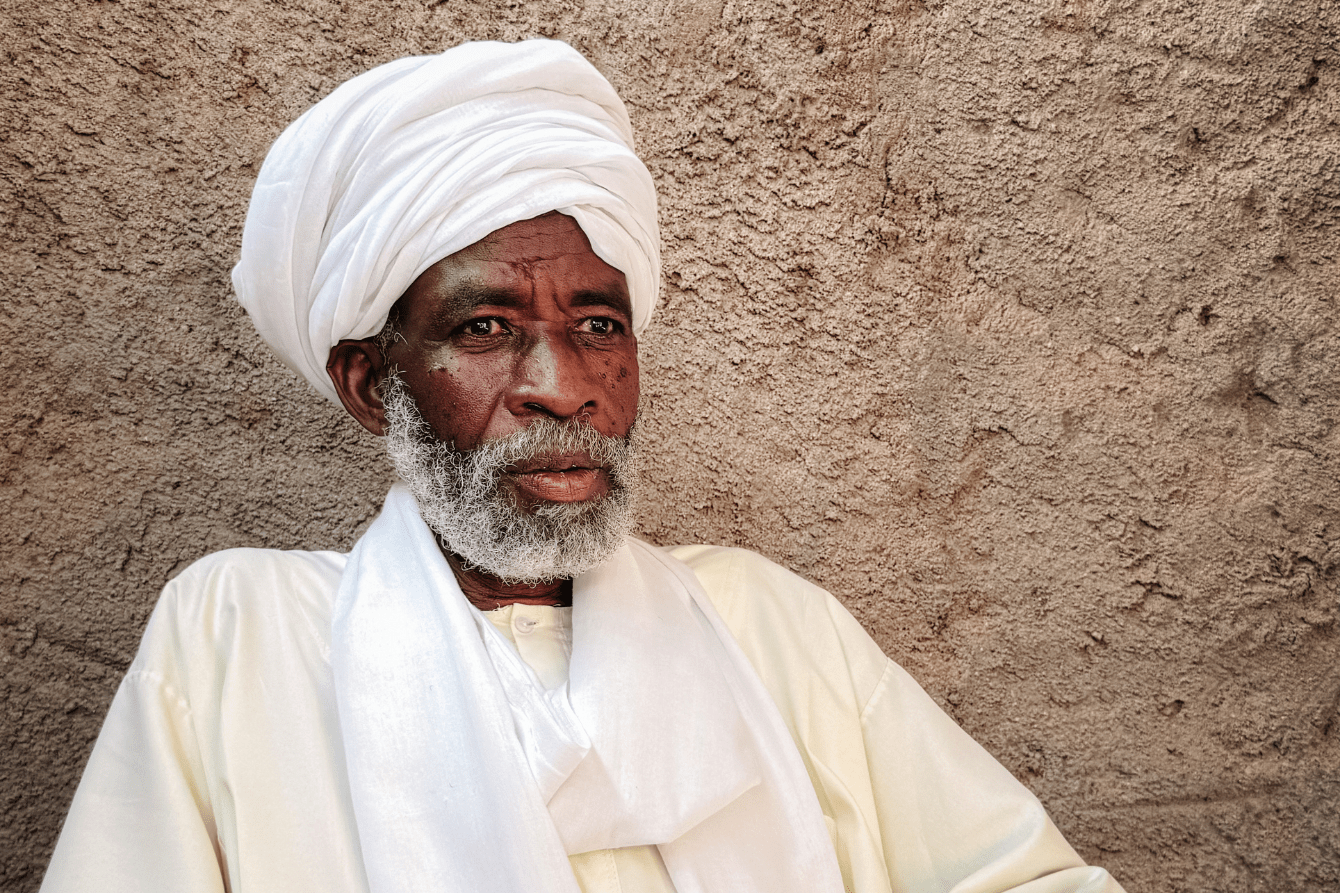

"No place is safe from the shells"

I think constantly, which makes it hard to sleep. My family is far away, the war is ongoing, and every day brings news of more deaths. My wife and two children are all in Kabkabiya, about 95 miles west of El Fasher.

I’ve been here for about eight months. I’m originally from North Darfur, and I’m 57 years old now. I came here to Iriba in eastern Chad from Adré, looking for work, but unfortunately, I couldn’t find a job. I left my family behind for this, so it’s difficult. My wife, my brothers, and sisters are scattered in different places. My children have been out of school for almost a year. They haven’t studied since last June. The war has destroyed everything.

I’ve been living with diabetes for 12 years, and before the war I had treatment in Khartoum, where I was before the war broke out. I spent a month there, then moved to Gezira state for five months before heading to El Fasher. Along the way, I faced harassment, beatings, threats, and humiliation from the armed forces.

As a diabetic, I need regular medical care, including eye, liver, and kidney tests every three months. But since coming here, I haven’t found any of these services. The treatment for diabetes is either too expensive or unavailable in Chad. I also need a specific diet, but here, things like vegetables and fruits are hard to find.

Educating my children is the most important thing for me now, but they are still in Kabkabiya, and I don’t know their fate. Sometimes there are airstrikes, and I worry they might be hit because the area is at war. No place in Sudan is safe from the shells.

I hope to return to Sudan. I want my children to go to school, for my family to be stable, and for Sudan to be better than it was before.

"Living in a house without walls"

We used to live an urban life, but we’ve been displaced from our cities. It’s hard to accept living in a camp. And even some of my family members are still in Sudan. They always say they won’t leave because Sudan is their country. We all hope the war will end soon, and we all want to return to our homeland.

The war took us by surprise. We left in such a rush that we didn’t have time to take any of our important belongings or memories. I left behind so many beautiful things in Nyala. My children lost their father; now they are orphans.

To get here we had to travel from Nyala to Tina. That journey usually takes two days, but it took us four. We passed through areas of fighting between the Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese Armed Forces. It was terrifying and exhausting.

I’ve been in this camp for 14 months. Living here, it’s like living in a house without walls or a fence. We still suffer from a lack of food, clean drinking water, proper education, hospitals, and medical care. Before the war, we would go to work and return home to our children, and we could easily meet our needs. But since the war started, life has become much more difficult.

I hope for a better future for my children. When the war in Sudan ends, I dream of having the chance to travel, completing my education, learning new languages, and finding a job. I want to provide for my children and support my family.

"What I witnessed in Zalingei will never leave me"

The war started in Zalingei, where I’m from, on April 15, 2023—the same day it started in Khartoum. We kept hoping it would end, but it didn’t. What I witnessed in Zalingei and during our displacement will never leave me. The memories are etched in my mind, and they haunt our children too. They are playing with sticks, pretending they have weapons. Children are living with the trauma of war.

In Sudan, we used to hide under beds to shield ourselves from the bombings. Those memories are painful, but here, we face even greater hardships. I’m 24 now, and I don’t know if I have a future. The children here, some are two or three years old, they deserve something better.

I’ve been living in this camp for a year and a month, since August 4, 2023. Life here is hard. We’ve only received financial aid five times since we arrived. Food and water are scarce. We normally get them every two days, but even sometimes we wait four days.

There are no jobs here, even for those of us who are educated. Our situation is critical. We're also facing a health crisis. There is no health center in the camp. We don’t have specialist doctors for heart or eye diseases, and many are suffering, including women needing obstetric care. In our previous camp, the health center didn’t have medicines.

We need psychological support. Many of us have lost family members to the war. People are missing, scattered across Sudan, or still in Darfur. The war has torn us apart, separating us from our loved ones. All of us here in the camp are missing someone.

If I had the choice, I’d rather return to Sudan, even if it meant dying there. That would be better than dying in this camp.