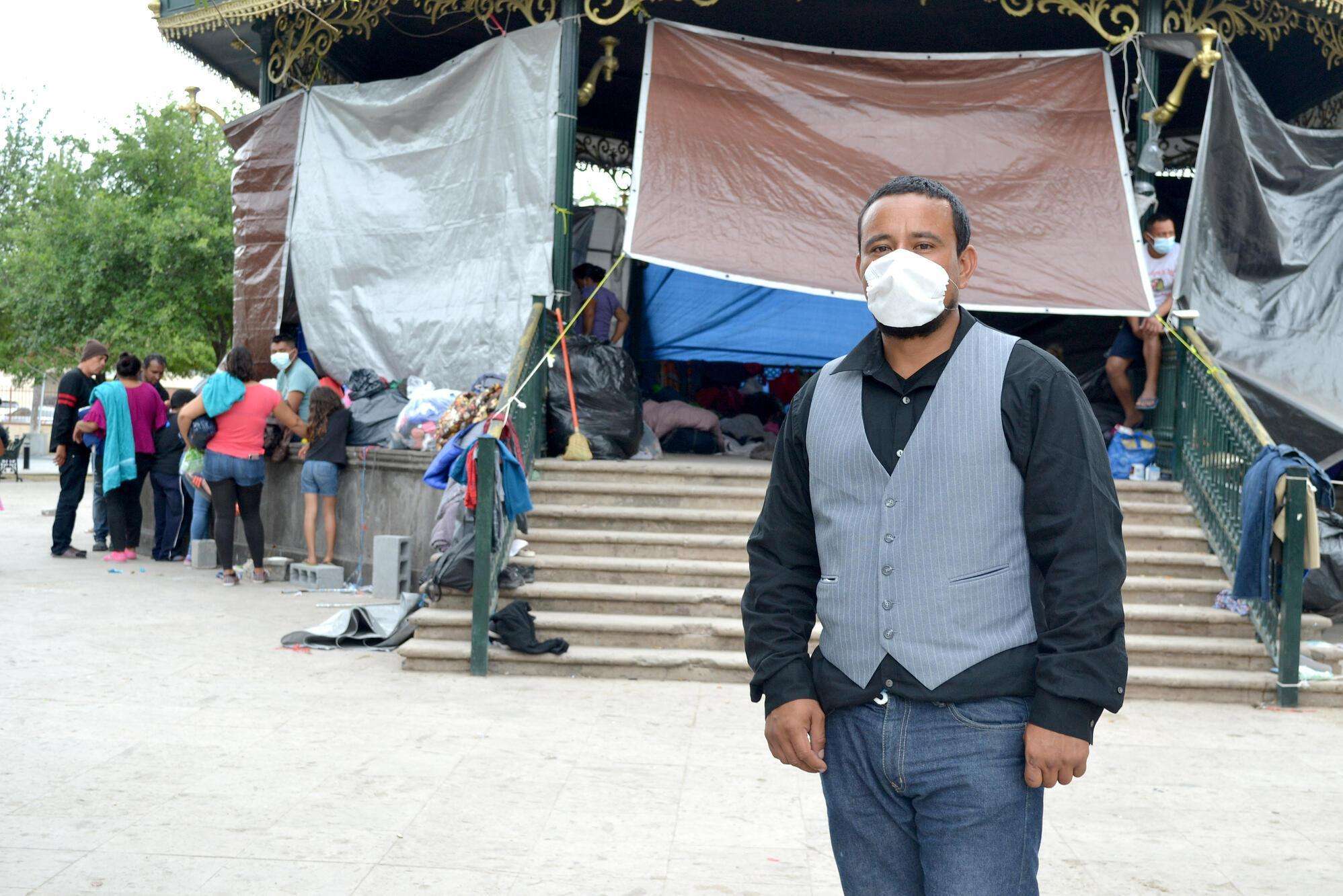

Migrants from around the world—from Central and West Africa to Haiti—are stranded in Reynosa, a dangerous city on the Mexico-US border. Between January and March this year, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) registered at least 150 people at the Senda de Vida shelter in Reynosa and provided 364 medical and 83 mental health consultations to migrants in the project.

The influx of people began in February 2020, when groups of people whose lives were in danger from extreme political violence fled countries including Ivory Coast, Guinea, Cameroon, Burundi, and Democratic Republic of Congo. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in Brazil, Chile, or Ecuador. There, exposed to greater risks, they traversed the continents by bus or on foot to the northern border of Mexico, arriving in Reynosa. More than a year later, these asylum seekers are still waiting for an answer on their applications, which were put on hold by the US and Mexican governments using the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse.

Many of these people left Reynosa out of desperation, putting themselves once again in harm’s way. They are seeking other ways to cross the border to be reunited with family members, to be in a safe place, and to move on with their lives. Some Haitians have already been deported under Title 42—which expedites the removal of all people who entered the United States irregularly, including those who applied for international protection.

Jean Pierre, Claire, and Paul awaited an answer on their applications for more than a year in Reynosa, but never got one. Their stories represent just a handful of the hundreds of migrants who are still stranded today in various border cities across the continent, invisible, exposed to violence, and living in poor conditions with no access to health care.

Jean Pierre, West Africa

Jean Pierre had to leave his home country because his life was in danger. He received political threats after trying to draw attention to corruption during a local election. Pierre fled to Quito, Ecuador, and made his way to Mexico on foot and by bus, facing different types of violence in each of the countries he had to cross.

“Leaving Colombia shooters attacked us. They took everything we were carrying, even our clothes, but we managed to get out of that situation alive and reach Panama, where we were living in three camps," he said. "After five months I was able to reach the border with the United States, and I have been waiting for more than a year to obtain asylum. All I want is to feel safe."

The young man first approached MSF after falling ill at the Senda de Vida shelter in Reynosa. Through the medical and social work services, he was able to connect with specialists, but because of the pandemic, his medical examinations were not completed. “Now all I can think about is my family. I want to get to a place where my life is not at risk so I can bring them with me,” said Pierre.

Claire, Haiti

After leaving Haiti, Claire and her family arrived in Chile. They were forced to leave their home country because they were protesting against the current government. She was threatened directly by police officers, who threatened to kill her children if she did not stop the anti-government actions, and was beaten by police officers, leaving her legs badly scarred. As the harassment increased, she decided to leave with her family as soon as she could.

Upon arriving in Chile, she felt it was best to try and reach the United States in order to live a peaceful life. She crossed Peru and Colombia. She walked for miles through Central America until she reached Tapachula, in southern Mexico.

When she arrived in Reynosa, she settled in the shelter and was regularly examined by MSF medical staff. “I was detained, I was assaulted, and yet I resisted so I could continue my journey until I got here. I feel a bit safer in the shelter but waiting so long just makes us lose patience because it seems like forever,” said Claire.

Paul, Burundi

In Burundi, Paul was imprisoned without trial. He managed to flee to Rwanda and from there to Brazil. He made his way up through Peru and became stranded in Panama. After two months, he was able to reach Nicaragua and went north to Tapachula. That was the journey Paul had to make from his home country after the military raided his house and raped his sister.

After Paul finished university, he worked in the administration offices of nongovernmental organizations and a hospital. Paul lived with his family and two children. “I want to go back and see my family and work there, but whenever I call home, they keep looking for me to hurt me. I'm afraid for myself and my children, so that's why I want to go to the United States legally.”

Paul has found support in MSF’s mental health service. Facing this long wait, many migrants like Paul develop symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression that have worsened over time. MSF is the only medical humanitarian organization that has psychologists working in the shelters. “I want to have a normal life again, go back to work. I don't feel like I’m home here,” said Paul.

*Names have been changed to preserve the identity of the individuals.