When Helen Tindall began working with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Cambodia wasn’t initially on her radar. But the extremely high prevalence of tuberculosis has made it a country she is reluctant to leave.

“Africa was my plan. Even in my interview I said that Africa was my preference,” Helen says. “But when MSF called they offered me Cambodia. I had to talk myself into accepting. But to be honest, there was no way I was going to turn it down.”

Helen has now worked as MSF’s TB nurse manager at Kampong Cham Provincial Hospital since October 2013. In that time, she has seen many challenges—such as “witnessing the extreme levels of poverty every day, the lack of resources and seeing people die from preventable diseases,” she says.

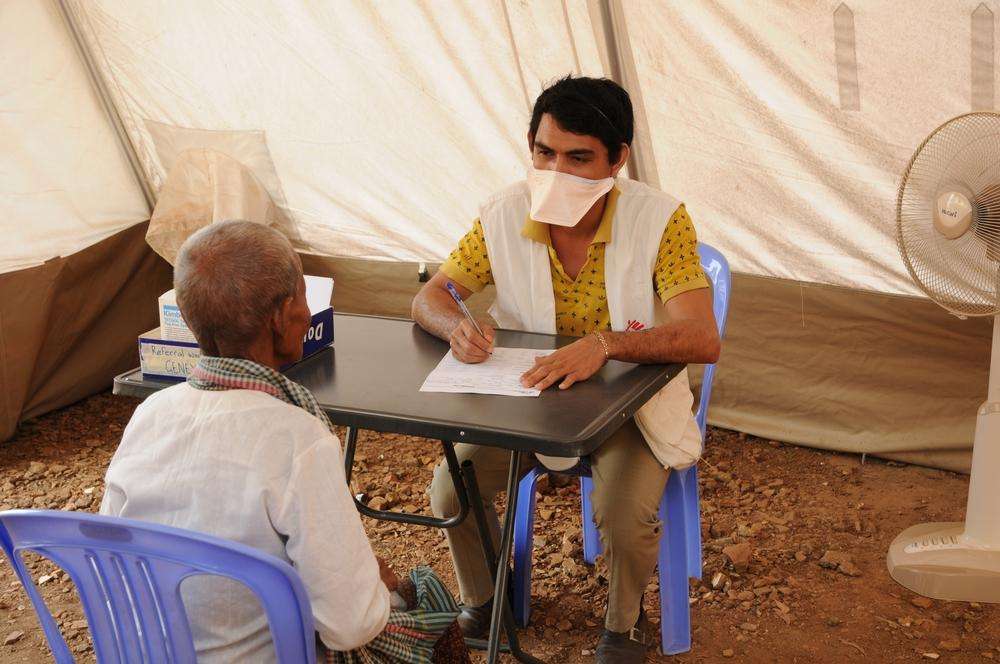

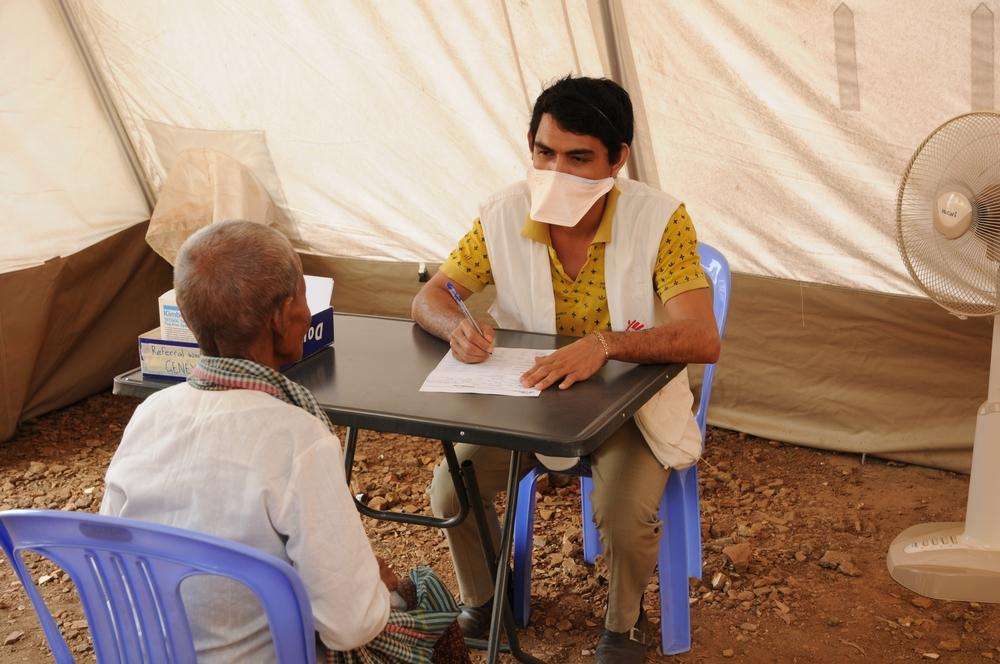

As the nurse manager for the TB department, Helen manages both outpatient and inpatient areas, the latter of which is divided into two subsections: one for confirmed cases of TB and the other for suspected cases and pediatrics, which are kept separate from the confirmed adult cases.

“I am also involved in the DR-TB (drug resistant) program, which very much has a home-based care aspect to it,” Helen says. “And I do a lot with health promotion—going out to schools and villages and raising awareness about TB.”

Due to the enormous prevalence of TB in Cambodia—the second highest in the world, with a rate nearing 800 per 100,000 of population—health promotion is critically important. “The prevalence is so high that everyone has some knowledge of TB. But it’s more basic knowledge,” Helen says. “It’s very much, ‘Yes we’ve heard of TB, we know it’s a cough,’ but that’s all.”

Because of high levels of poverty, malnutrition also plays a devastating role in the rate of TB in Cambodia. “Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty, and malnutrition is very connected to it,” Helen says. “People are malnourished, so their immune system is suppressed. And then with TB, you don’t eat so you become weaker,” she says. “People who weighed 50 kilograms [110 pounds] now weigh 35 kilograms [77 pounds] or even 30 kilograms [66 pounds], and children who are badly stunted look five years younger than they are.”

An example of this was a 13-year-old boy that Helen got to know early in her mission. “I didn’t believe he was 13,” she remembers. “I actually thought he was seven, he was that malnourished. You could see every breath he took. The skin was sucking in through his ribs. I went to see him every morning for a week, but when I arrived one day his bed was empty. He was too weak and had died. It was a real shock.”

The poverty and lack of resources also reveals just how difficult the battle against communicable diseases can be, such as the slow rise of MDR-TB (multi-drug resistant) which, while not yet critical, cannot be ignored.

The contrast between treatment options for MDR-TB in developed and developing countries is stark. In developed countries, if you have MDR-TB you are placed in isolation for as long as six months or more, until none of the bacteria is left in your body—something that must be confirmed in a laboratory confirmed.

However, says Helen, “Here in Cambodia, once your clinical condition is stable, treatment has commenced without problems, and treatment support is arranged in the community, [patients are often simply sent] home and are advised to stay away from your family, to not eat with them, to sleep apart from them.” Without oversight, lack of adherence to treatment can increase drug resistance, and puts family members and others at risk of infection as well.

However, despite the challenges, finding and treating people with tuberculosis in Cambodia does and will continue—and so will Helen’s work. Despite her original desire to work in Africa, Helen asked for her Cambodia mission to be extended. Her request was recently approved.

“I think there’s hope for the overall picture with TB in Cambodia,” she says. “In 2012, the World Health Organization announced that TB rates in Cambodia had halved in the past decade, and while we still have one of the highest rates of TB in the world, they continue to decline. I think MSF's involvement has played a part in this success.”