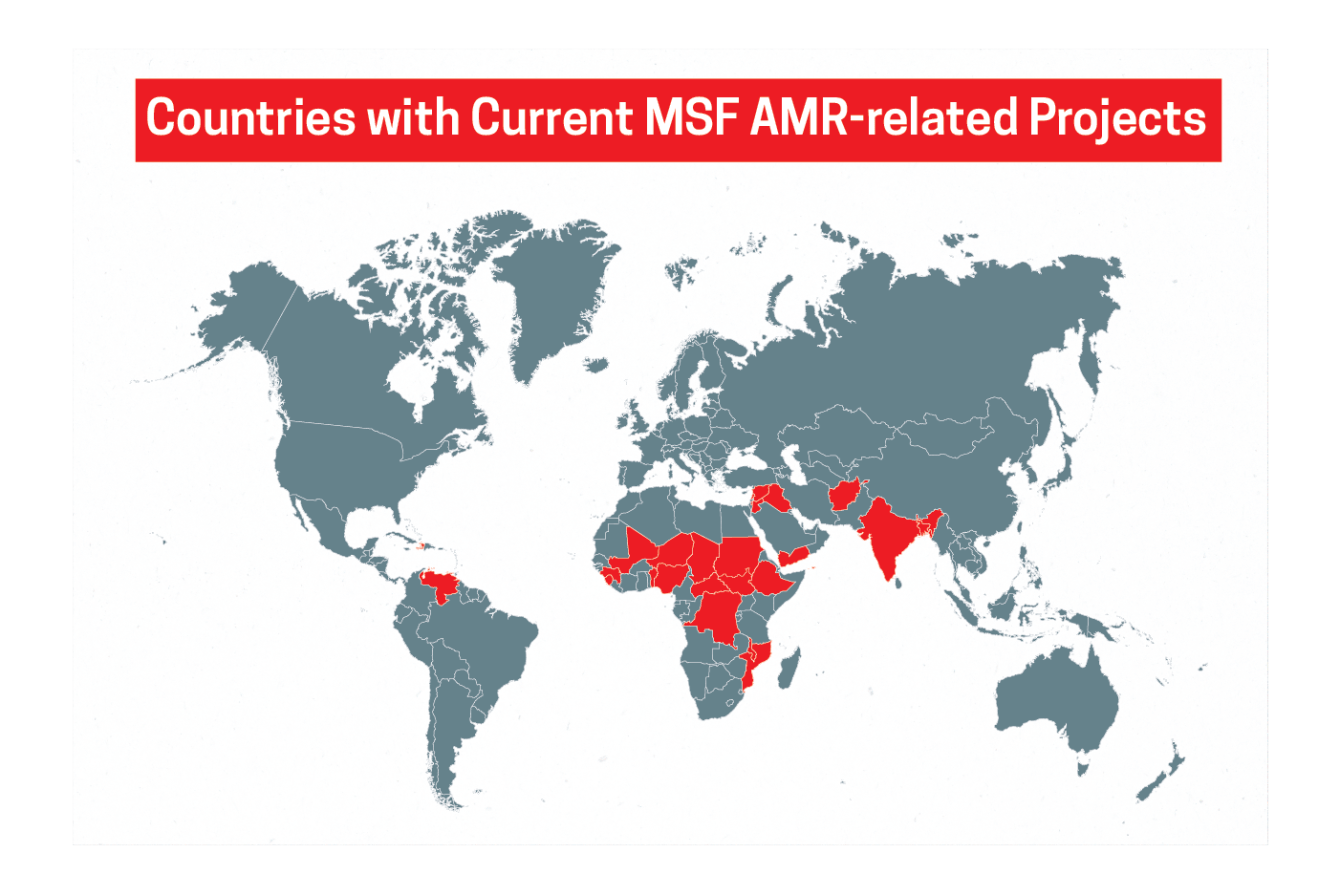

Teams with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) work in more than 70 countries across the globe every day, treating a range of injuries and illnesses like war wounds and burns, infectious diseases like HIV and tuberculosis (TB), and malnutrition. But in some cases, treatments that once saved people’s lives aren’t working anymore.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—when microbes like bacteria, viruses, and fungi evolve and survive despite the antimicrobial medicines, such as antibiotics, used against them—can make medical care less effective and much more difficult, prolonged, and costly for patients and treatment providers.

AMR is recognized by the World Health Organization as a top-10 public health threat. It caused 1.27 million deaths in 2019 alone, making it a leading cause of death worldwide, with low-resource settings bearing the greatest burden. If nothing is done to curb resistance, it could become the leading cause of mortality, with 10 million deaths per year globally by 2050.

What causes resistance

The development of resistance is a natural process of evolution as microbes attempt to survive whatever is trying to kill them. Unfortunately, the inappropriate use of antimicrobial medicines in humans, animals, and agriculture supercharges this process, speeding up the loss of effective treatments and the emergence of more deadly and destructive infections.

In order to prevent, detect, and respond to resistant infections, health systems need the following:

- Infrastructure and supplies for effective infection prevention and control (IPC) practices, along with proper vaccination and water, sanitation, and hygiene.

- Health care workers trained in IPC and antimicrobial stewardship (the appropriate use of such drugs).

- Access to laboratory-based diagnosis and surveillance to identify exactly what kind of infection a person has and which treatments, IPC protocols, and public health measures are appropriate.

- Affordable access to the right treatments at the right time.

AMR in the Middle East

“MSF’s focus on AMR began in the Middle East when we started receiving war-wounded patients with open fractures that were more susceptible to infections like osteomyelitis, a bone infection. From the first day—the first patient—we had to face this problem, because the bacteria we were dealing with were highly resistant to many drugs.”

— Dr. Nada Malou, MSF microbiology advisor

Why low- and middle-income countries are so affected

In most humanitarian contexts and many low- and middle-income countries in the world, these key components of quality health care are compromised, scarce, or entirely out of reach.

People in these countries experience the highest rates of AMR and infectious diseases globally but are the least likely to have access to the medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics they need. In humanitarian settings, other factors compound the AMR crisis. Conflicts or natural disasters, for example, can result in traumatic injuries that can easily become infected, force people to take refuge in overcrowded settings where diseases can spread rapidly, rupture supply chains, and shatter already-fragile systems for health and water, sanitation, and hygiene.

The US has a National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, but some countries have no national action plans to tackle AMR and many more lack the resources to carry them out. Initiatives like the AMR Multi-Partner Trust Fund—meant to drive financing for the implementation of national action plans—remain only partially funded. And the limited funding available to address AMR through mechanisms such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria and the World Bank’s Pandemic Fund falls far short of what is needed in both magnitude and the kinds of programs supported.

In high-income countries including the United States, many of the most ambitious proposals for curbing the spread of AMR focus on supporting research and development of new antimicrobials. While new medicines are crucial and will always be needed to treat people for new infections as resistance develops, innovative treatments will be of no use if they aren’t promptly accessible to the people who need them most—and they are far from all that is needed to address this global crisis.

A newborn in Bentiu

"Last November, a one-month-old premature baby boy, born in our facility was admitted for neonatal infection. A blood sample was collected and while waiting for the results, the doctors prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotics. In 48 hours, the microbiology tests revealed that the patient had klebsiella pneumonia, a dangerous infection with a tangible risk of death—especially for patients who have been taking certain antibiotics for a long time...

MSF’s role in addressing AMR

For the past decade, MSF has been implementing a concerted, multidisciplinary approach to address AMR in our operations which includes training, resources, and support for IPC and antimicrobial stewardship, and laboratory-based diagnosis.

As part of our effort to expand access to reliable diagnosis, our teams have developed some new technological innovations that can be used in the types of lower-resource settings in which MSF teams work, including the Antibiogo smartphone app that allows non-expert lab technicians to measure and interpret test results and the Mini-Lab, a simplified, portable bacteriological laboratory.

Our teams have seen—and are documenting through research—how such targeted, practicable interventions to strengthen health care against AMR improve outcomes for patients and communities. It is essential that these approaches be scaled up around the world, alongside and in addition to research and development for new antimicrobials.

What can the US do to help combat AMR globally?

While MSF works to prevent and address AMR in its projects, drug resistance is a global challenge that requires cooperation and investments from different countries and sectors.

Commitments made by the global community at the first United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHLM) on AMR in 2016 have not translated into action at nearly the pace or scale required. This is due to the lack of concrete targets to measure progress and hold governments accountable and the lack of funding available, particularly for low- and middle-income countries.

When US leaders come together with other countries later this year at the second UNHLM on AMR, they must be ready to make more substantive commitments to address drug resistance at a global level—backed with resources—and take concrete steps to support countries that face the greatest challenges.

The US can help lead a global response to this health emergency by committing to provide financing, technical assistance, and political support to:

1. Increase health systems’ capacity for IPC and antimicrobial stewardship.

The US can help provide countries with the health infrastructure, training, and supplies they need to stop transmission and inappropriate antimicrobial use like giving out the wrong antibiotics for a particular infection.

2. Expand access to laboratory-based diagnosis and surveillance.

The US can help equip more communities with the laboratories they need to inform patient care, IPC strategies, and public health policymaking.

3. Promote universal access to existing and new medical tools and technologies, including antimicrobials, diagnostics, and vaccines.

To make existing tools more accessible and affordable, the US can facilitate manufacturing initiatives in low- and middle-income countries; help countries track access and strengthen forecasting and supply chain management; and support regional and international pooled procurement initiatives. To ensure access to future tools, the US should invest in research and development that centers on urgent public health needs, attach conditions to research and development funding that assures resulting products are affordable and accessible—which the proposed PASTEUR Act does not—and prioritize investment in public and nonprofit research and development initiatives, which are most conducive to access, stewardship, and the kind of research collaboration needed to overcome scientific bottlenecks.

4. Enable all countries to develop and implement national action plans for AMR and ensure that the global response to AMR centers on the needs of the most affected communities.

The US can help ensure that international financing mechanisms are robustly funded; integrated with existing programs for development, health, and pandemic preparedness and response to reduce fragmentation and administrative burdens on low- and middle-income countries; and free of requirements for co-financing. The US can also facilitate meaningful participation by civil society in the formulation and governance of AMR-related initiatives; ensure that targets for global progress against AMR focus on meeting the needs of affected communities; and support evidence generation in low- and middle-income countries to inform and guide response strategies.

PASTEUR Act analysis

The PASTEUR Act is not the right way to spur antimicrobial innovation. Read MSF's analysis to learn why.

More on antimicrobial resistance

May 23 01:40 PM

Doctors Without Borders releases 2023 activity report on antimicrobial resistance

Global action must be taken to avert a looming humanitarian crisis.

Read More

May 15 02:20 PM

MSF statement and position paper on antimicrobial resistance for UN High-Level Meeting

We have treated many thousands of patients with drug-resistant bacterial infections, and have noted with alarm the increasing rates of resistance.

Read More

November 15 03:52 PM

Antimicrobial resistance must be addressed in pandemic preparedness and response

AMR is recognized by the World Health Organization as a major public health threat.

Read More