An MSF-sponsored panel discussion held at the Graduate Center, CUNY

An MSF-sponsored panel discussion held at the Graduate Center, CUNY

|

Good evening, ladies and gentleman. Thank you for coming tonight. My name is Anne-Valerie Kaninda. I am the Medical Advisor for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières in New York. As you know, more than 34 million people are infected with HIV. 95% of those infected live in the developing world and do not have access to adequate treatment, to effective treatment of opportunistic infections, or antiretroviral therapy, even though these treatments are available. 8,000 people die from AIDS every single day. Meanwhile, the international community is telling AIDS patients in the developing world, "I'm sorry, you will die because treating you is not cost-effective." For us physicians, this is shocking. It is contrary to the most basic medical ethics. We do not agree to simply write off 34 million people's lives when we know that treatments exist. Tonight we have four people working in our field projects in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. They are all fighting to provide adequate care and treatment to people living with HIV/AIDS. They are going to share with us their experience.

Antiretroviral Treatment in Ukraine: The Bitter Pill

[Read]

Konstantin Lezhentsev, M.D., MSF-Ukraine, is an advocate for affordable AIDS treatments in the Ukraine where he works on MSF's HIV treatment program for mothers and their children.

Access to Affordable AIDS Medicines in Thailand

[Read]

Onanong Bunjumnong, MSF-Thailand, leads MSF's Access to Essential Medicines Campaign in Thailand, where MSF has been treating people with AIDS for 6 years.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS by ARVs: The Experience of Cameroon

[Read]

Rose Mougnutou, M.D., MSF-Cameroon, has been treating people with AIDS with anitretrovirals at the University Hospital of Yaounde for over 3 years. She currently works in an MSF pilot project providing antiretroviral therapy.

Treating HIV/AIDS in Kenya

[Read]

Chris Ouma, M.D., Action Aid Kenya, treats people with AIDS in the slums of Nairobi and has been an outspoken critic of international trade agreements that have kept antiretrovirals out of the reach of his patients.

Questions from the Audience

[Read]

Good evening, dear friends. My name is Konstantin. I'm a medical doctor working in an MSF-Holland project in Ukraine. I myself am one of this country's 50 million citizens. Ukraine is now known in Eastern Europe as an epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The AIDS epidemic in the Ukraine is developing from a few cases in 1987 into a full-blown epidemic that has touched all-levels of Ukrainian society, including the most productive… our youth.

At present, as of April 2001, according to the official statistics, there are 38,109 people infected with HIV AIDS in Ukraine. These official figures account for those whose diagnosis was confirmed by double testing. However, the UNAIDS experts estimate that there are more than 300,000 people living with HIV in Ukraine. By the year 2014, they estimate that there will be 1.5 million people infected with HIV. The experts estimate that the cumulative death toll from AIDS is 9,400 people.

The epidemic first affected a marginalized group of Ukrainian society—intravenous drug users. Around 60-80% of HIV+ people were infected through IV drug use. Although injection drug users still form the majority of people infected with HIV, the epidemic has reached a new phase. There is now substantial growth in both heterosexual and mother-to-child transmission rates. The majority of HIV+ people in Ukraine are under 30 years old.

Despite the fact that Ukraine officially recognized the HIV/AIDS situation as an epidemic, that the State Committee on HIV/AIDS was formed, that since 1995 major donor international organizations started a bunch of programs concentrated on prevention only, adequate medical care including ARV treatment, effective treatment and prevention of opportunistic infections, palliative care, and modern methods of diagnostics are not available for people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine.

Despite the fact that major pharmaceutical representatives in Ukraine are constantly expressing their desire to decrease the price of ARV drugs (antiretroviral drugs) and to start fruitful negotiations with the Ukrainian government about the price decrease, there has been no actual decrease. The lowest price offered by the government for the year 2001 was $ 9,500 per patient per year for combinations of Nelthinavir-Combivir, Indinavir-Combivir, or Nevirapin-d4T-ddI, the combination that has been successfully improving the quality of life for patients living with HIV in the developing world. The health care budget for the year 2000 for all HIV programs including prevention programs was $ 2.2 million. The amount of funds allocated for treatment was $164,000 for adults and $180,000 for children.

These figures underline the crucial need for immediate implementation of all existing mechanisms for a price decrease to make HIV/AIDS treatment available for all those who need it in Ukraine.

Ukraine was the first country in Eastern Europe to officially recognized its responsibilities in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Ukraine was one of the countries that initiated the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on HIV/AIDS. Our closest neighbors from Eastern Europe, such as Poland, are providing treatment for their HIV+ citizens. International agencies assessing the pharmaceutical capacity of Ukraine describe Ukraine as a country of generics, reflecting the high production and importation of generic drugs such as antibiotics and antifungal drugs. Ukraine should not be permitted to get stuck in the continuous circle of excuses given by pharmaceutical companies and some international agencies. It is obvious from the experience of other countries that a number of excuses for not providing treatment are always available. They are: Build an infrastructure and system capacity first. Poor compliance from marginalized HIV+ individuals. (That means discrimination of intravenous drug users and homeless people). Prevention should be the mainstream of an effective response. These are the standard phrases that are used on the global and regional levels, but what that really means is that HIV+ people will die.

People living with HIV in Ukraine cannot wait for all these negotiations to take place in standard process. They do not have time for this, and I, as a member of MSF, and as a Ukrainian citizen, cannot allow these people to die on the side of the road of a wide range of prevention interventions.

The hopes of my colleagues and partners, people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine, people helping others to overcome the social, psychological, and economic problems associated with HIV/ AIDS and dying from the lack of treatment in Ukraine, cannot be eclipsed by general phrases of "examining alternatives for increasing access and affordability of HIV/AIDS related drugs." The possibilities should not be examined, but implemented immediately in all countries where treatment is not affordable for those who need it. The main obstacle for making treatment available is the concern that treatment is not possible. Treatment significantly improves the quality of life of those living with HIV in the developing countries. There is no excuse for not providing it due to economic reasons.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS is feasible and the cornerstone of effective prevention. Moreover, the development of the HIV epidemic in Western countries was effectively prevented only when treatment was implemented for HIV+ people. Until the stereotype of an HIV diagnosis as a death sentence changes, there is no way that preventative messages will be effectively accepted by the general public and effective change in risky behavior will occur.

Poor infrastructure and compliance from patients should not be an excuse for the pharmaceutical companies and the governments for not making treatment affordable. A more appropriate response would be overcoming the obstacles to a good infrastructure by involving the NGO sector and not permitting the discrimination of certain, marginalized groups of patients such as HIV-positive drug-users and homeless people.

From the very beginning of the development of the MSF project on preventing mother-to-child transmission in Ukraine we have been working hand-in-hand with people living with HIV/AIDS. These people became our close partners, professional and motivated. The experience of our collaboration showed that they are the real force that can effectively defend their human rights (first of all the right for adequate medical care), that is able to fill the infrastructure gaps and provide compliance of patients for treatment and be a relevant partner for the government on all levels in revising existing strategies in order to increase their effectiveness.

I want to share with you my honor and respect for these people, their courage and willingness to help others. I want to honor those Ukrainian doctors who do their best to overcome poverty, absence of information and discriminating attitudes towards people with HIV and who provide adequate help to their patients.

Natasha.

I want her to be able to help others as she does now.Dima.

My colleague. I want him to be able to give adequate treatment to his patients.Alya.

My friend and colleague. I want her to stay with us.Natasha.

My friend and colleague. I want her to see her son growing.Sergei.

My friend and colleague. I want all of his dreams to come true.Ivanka...

During my first exploratory mission with MSF two years ago she was born. I was so excited to be a part of a powerful international organization that I looked at her and was very optimistic about her future, about confirmation of her HIV- negative status, about her life … Ivanka died at the age of two years. She was born HIV-positive just a few months before MSF's project on prevention of mother to child transmission had been started in her region. She was not a rapid progressor of HIV-infection, but she had strong indications for starting ARV-therapy.My patients and my colleagues are tired of continuing negotiations, of nice smiles of healthy patients from the pharmaceutical commercial posters hanging on the walls of the hospitals where people die from lack of medicines, of expired drugs given as a "charity humanitarian donations" from pharmaceutical companies.

There is no excuse for not providing treatment to people, the treatment is feasible and is a right of every human being regardless of his or her social and economical status.

As a medical doctor and MSF member, as a citizen of Ukraine, I can confirm that until the treatment will be provided for all people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine, until the term "death sentence" is no longer associated with HIV infection, all the huge efforts of the main international organizations focusing on prevention will not be effective.

Treatment is a cornerstone of prevention, the crucial aspect in changing ideological stereotypes toward HIV in society and thus the real "cost-effectiveness" of combating the HIV/AIDS epidemic in my country and worldwide.

Question:

How are people living with HIV in the Ukraine organized?During the past year, crucial steps were made in their organization. Many are now a part of the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS. The network was created at the same time as the AIDS epidemic was given political recognition in the Ukraine. They set up self-support groups and fill in the gap of the infrastructure. Representatives of the Network are part of the official delegation of Ukraine to the UNGASS on HIV/AIDS. This delegation includes the Vice Premier Minister of Ukraine and the Minister of Health.

Question:

What is the situation in the other former Soviet Republics, and how does it compare with the Ukraine?The Ukraine is the epicenter of the epidemic. 1% of the population is infected. In Russia, there is also rapid progression. Itravenous drug use is the main route of transmission. The Baltic Republics have fewer cases. Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan are now only developing their statistics. Countries such as Bella Russia have far fewer cases than Ukraine or Russia.

Question:

What is the average age of intravenous drug users in Ukraine?Under 30 years old.

Access to Affordable AIDS Medicines in Thailand

Delivered June 21, 2001 by Onanong Bunjumnong as part of the MSF-sponsored panel discussion Dying from Lack of Treatment: The International AIDS Crisis.

First I want to thank everyone for coming tonight. My talk will be about access to affordable AIDS medicines in Thailand. I will divide my talk into two parts. The first will focus on the pricing barrier while the second will address patent issues.

In Thailand, it is estimated that one million people are living with HIV/AIDS. The total population of the country is 62 million. Only 5% of every 100,000 people living with HIV in Thailand have access to affordable medicines or antiretroviral treatments. One of the reasons that people in Thailand and other developing countries continue to die of AIDS is due to the fact that they cannot afford antiretrovirals or other essential medicines.

People with AIDS in Thailand can access antiretroviral treatments from the following sources:

- The first way to get ARVs is to buy them at the market price. The following is an example of the cost of triple therapy, the standard combination of antiretroviral treatments. If one bought d4T from Bristol-Myers Squibb, 3TC from Glaxo SmithKline, and neverapin from Burinko, it would cost $15/day. A monthly supply would cost $450. The minimum wage in Thailand is $2.60/day and $80/month. It is impossible for Thai people to pay for their own medicine. Even if they borrowed money from family and friends, they would have to do so for the rest of their lives.

- The second way to access antiretroviral treatment is through a government subsidy. AZT and ddI are subsidized since they are on the Essential Drug list in Thailand. The third drug in triple therapy would have to be paid for from one's own pocket.

- The third way to access ARVs is through clinical trials. There are several clinical trials currently running in Thailand. The first is through HIVNAT (HIV- Netherlands-Australia-Thailand), which covers 1,000 people. Hospitals and hospices run trials that cover 200-300 people.

- The fourth way to access ARVs is through the CDC (Communicable Disease Control) of the Thai Ministry of Health, which covers 3,000 people.

- The final way to access ARVs is through two MSF ARV projects in Thailand that cover 70 people.

Only 5,000 out of 100,000 living with HIV have access to ARVs in Thailand. Only 300 can afford to pay for their own medicines.

The following are a few quotes on this issue. The first is from a woman now in MSF's ARV program who went blind from her HIV infection. She said, "If I could have afforded to pay for my antiretroviral treatment three years ago, my health and my life would be much better, and I would be able to see."

The next is from an AIDS activist. He said, "If I could have afforded to pay for my antiretroviral treatment, my husband would still be alive today."

It is really tragic because we know that treatment exists, but people cannot get access to it because of its high expense.

In Thailand, we rely on generic drugs. In 1998, Pfizer sold fluconazole (a drug for cryptoccocal meningitis, an opportunistic infection) for $6 per capsule. The price of generic fluconazole is only 15 cents per capsule, however.

In July 1992, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) obtained a patent on ddI, one of the antiretroviral drugs commonly used in triple therapy, to maintain a monopoly on the drug. The Thai Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO) was unsure of ddI's patent status, due to the complicated process of the Thai Intellectual Property Department. The GPO researched ddI formulation for twelve years. In February 1998, the GPO planned to launch generic production of ddI. Six BMS representatives flew to Thailand and stopped them in their tracks.

In November 1999, the GPO asked the Ministry of Health to issue a compulsory license for the generic production of ddI under the Thai patent law. A compulsory license is a license for generic production without the permission of the patent holder. The Thai government did not respond to the request.

In December 1999, 68 NGOs and 100 people living with HIV demonstrated in front of the Ministry of Health. They supported the GPO and asked the government to issue a compulsory license for generic production of ddI. After days and nights demonstration, the Ministry of Health agreed to allow the generic production of ddI, but only in powder form, since the tablet was patented.

We know that the reason the Thai government would not allow generic production of the tablet because it was afraid of United States trade sanctions.

One month later, the NGOS and the Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS demonstrated in front of the U.S. Embassy. They requested a clear statement from the U.S. President ensuring that the U.S. would not take any punitive action against the Thai government if they issued a compulsory license. A proposed letter, signed by the Chairman of the Network, was sent to the U.S. President.

Ten days later, the U.S. trade representative responded with a letter stating that the U.S. would not object to a compulsory license to help the Thai healthcare crisis. Finally, Thailand had a green light to issue a compulsory license for the generic production of ddI, but the government still refused to do anything.

At this point, activists and people living with HIV were extremely frustrated. In order to take the powder version of ddI, one had to mix it with water. This often disclosed one's confidentiality because others recognized the powder as AIDS medication. People living with HIV in Thailand are highly stigmatized. Having one's status disclosed only leads to discrimination.

The NGOs, people living with HIV, pharmacies, technical experts, lawyers, and doctors, believe that since the research and development of ddI itself was done by the U.S. Institute of Health, BMS had no right to obtain a patent in the first place. The NGOs and people living with HIV filed a lawsuit against BMS. They feel that the intellectual property laws are unfair to developing countries. A complaint was filed by the Thai court on May 11, 2001. A copy of the complaint was also sent to a BMS representative in Thailand. We are now waiting for their response.

I am standing here today as a representative of an international humanitarian organization and as a Thai citizen. I strongly believe that antiretroviral treatment is feasible and possible in Thailand. I also believe that prices of anti-AIDS medicines must fall to affordable levels and safeguards within TRIPS agreement (which include compulsory licenses) must be practically and effectively implemented. I also believe that political will is desperately needed to overcome treatment barriers for the poor.

Onanong Bunjumnong holds a Masters Degree in Health Sciences. She joined MSF in Bangkok in January 2000 where she first worked as an assistant to the antiretroviral project that MSF started there. The goal of the MSF HIV program in Thailand is to improve healthcare for people living with HIV/AIDS in central Bangkok and in three surrounding districts. It includes several components, among them a pilot antiretroviral project and a lobbying campaign with national activist groups and NGOs focusing on the price of essential medicines for people living with HIV/AIDS. Onanong is now a Communications Officer, specifically focusing on access to antiretroviral treatment.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS by ARVs:

The Experience of Cameroon

Delivered June 21, 2001 by Rose Mougnutou, M.D., as part of the MSF-sponsored panel discussion Dying from Lack of Treatment: The International AIDS Crisis.

Rose works in an MSF pilot project in Cameroon providing antiretroviral therapy to HIV/AIDS patients.

My presentation will consist of three parts. The first is an overview of the HIV/AIDS situation in Cameroon. The second deals with my experience treating HIV+ patients in Cameroon. The last deals with the conclusions I have drawn from my experience.

Cameroon is a country located in Central Africa at the equatorial level. Out of fifteen million inhabitants, almost one million people in Cameroon are HIV+. This represents 11% of the sexually active population.

Here is an overview of the AIDS statistics on Cameroon.

- 937,000 people are living with HIV.

- 52,000 people died from the disease in 1999.

- 91,000 children were orphaned due to AIDS in 2000.

- 5,168 new cases of HIV were transmitted in 2000.

- 90% of them were sexually transmitted.

- 10% were caused by mother-to-child transmission.

- 5,000 children are living with HIV in 2000.

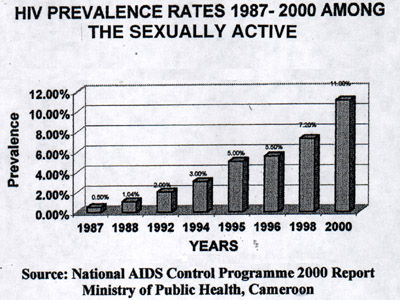

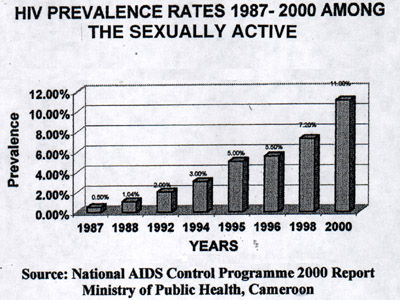

This graph illustrates the evolution of prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the sexually active population from 1987 to 2000:

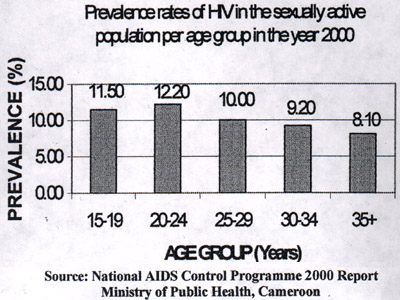

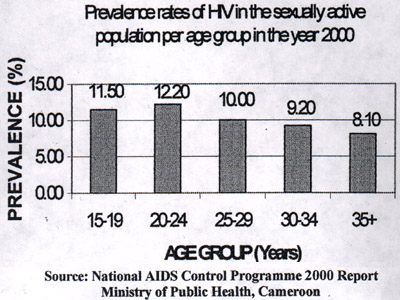

Here we can see the prevalence by age groups: the most affected group is the 15-25 group nevertheless, all age groups are affected.

The PRESICA project (Prevention of AIDS in Cameroon) is a collaboration between the Public Health and Defense ministries of Cameroon. It is financed by the Research Institute for Development (France), the European Union, and The National Research Agency for AIDS (France). It has enabled the management of a cohort of nearly 400 patients who now have access to voluntary screening, treatment and prevention of opportunistic and non-opportunistic infections, and psycho-social follow-up.

From these 400 patients, the PARVY project selects people for ARV treatment.

The PARVY project (The Antiretroviral Project of Yaoundé) is a collaboration between PRESICA and MSF Switzerland. It started in January 2001. Its objective was to lower the morbidity and mortality rate amongst PRESICA HIV/AIDS patients by providing a specific ARV treatment at no charge. To this day, among the 150 patients who will be included in the next 2 years, 17 are on ARV with a clinical and biological (VL CD4) follow-up as well as therapeutic surveillance. The treatment is sponsored by the project and provided by 6 doctors who specialize in HIV/AIDS.

The PARVY project has been functioning now for 6 months and with only 17 patients it is currently too soon to do statistical evaluations on the benefits of ARV on these patients. To our clinical eyes we can say without fear and unequivocally that the lives of our patients have improved in the past 6 months.

We have noted that there is decrease and almost disappearance in opportunistic and non-opportunistic infections in these patients. There is also a marked increase in appetite and a rapid and considerable weight gain (with a average of 3-5 kilos - 6.6 - 11 lbs. per week).

Here I would like to mention the particular case of a 30 year-old military patient abandoned by his siblings due to his illness which had completely debilitated him to the point of immobilization. He regained 15 kilos (33 lb) during his first month of treatment on ARVs. He now has regained his autonomy and mobility. Today he comes to his consultations as an outpatient.

Generally, most of our patients have a renewed will to live to take on professional activities again since they have reacquired their independence and are no longer a burden on their families.

Nevertheless, even in this short period of 6 months, we have identified problems. They are:

- The rigorous treatment criteria excluded some of the patients that would have wanted to benefit from the PARVY program. This brought the management team to lighten certain conditions of inclusion to the project such as financial factors as well as geographic distance of the patient's home.

- The ARV treatments require good nutrition. Some patients refuse to pursue treatment because they are financially unable to cover the cost of food that is of an appropriate quality or quantity.

- Certain patients refuse to share the secret of their illness with their loved ones. This obliges them to hide the fact that they are taking ARV treatment, consequently increasing the risk of forgetting to take their treatment and/or refusing to take it.

Recently the price of ARVs has decreased considerably due to an accord between the Cameroon government and some pharmaceutical companies. We now follow, in addition to our PARVY patients, 20 people on an outpatient basis. They buy themselves their ARV treatment for a monthly cost of $100. These patients are also in need of medical case management (i.e. treatment of opportunistic infections and non-opportunistic infections, CD4 counts, viral loads etc.). All of these expenses are incurred from their own pocket and weigh heavily.

In conclusion, antiretroviral treatment greatly improves the lives of patients with HIV/AIDS. With the hope that the price of ARVs continue to drop and, in the long run, become free for everyone with AIDS in Cameroon. Access to treatment for opportunistic infections must remain a priority. We must also continue to exert pressure to decrease the cost of the biological follow-ups.

My recommendations for the PARVY project are as follows:

- We hope to further decrease the cost per patient.

- We also hope that patients can be recruited from anywhere in the country.

- At the national level, we must work on poverty reduction. Patients know that antiretrovirals exist, and are frustrated that they cannot access them. We must also work to empower patients living with AIDS. This will help them reach economic independence and break the silence.

Dr. Susan Rose Mougnutou graduated from the University of Paris Medical School. She is a specialist in internal medicine, dermatology, and sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, she works at the University Hospital in Yaoundé, the capital city in Cameroon. She has been working specifically on the PARVY project for the past six months. She has worked in Cameroon for ten years, three years on the PRESICA project.

Treating HIV/AIDS in Kenya

Delivered June 21, 2001 by Chris Ouma, M.D., as part of the MSF-sponsored panel discussion Dying from Lack of Treatment: The International AIDS Crisis.

Thank you very much. My presentation will be in three parts. In the first part, I will give a brief background on the AIDS situation in Kenya. In the second part, I will briefly mention some of the ways that our country can go forward in managing the epidemic. In the last part, we will look at some of the more positive aspects of HIV in Kenya.

Kenya's population as of December last year was 29.5 million. The sexually active population (between 15 and 49 years old) was 14.3 million people. The GNP was $340 and 43.6% of the population was economically active, which just underscores the number of people under 15 years old. Life expectancy is 52 years old, this is down from 63 in 1984. The proportion of the urbanized population, which is considered at higher risk for HIV, is 30%, which is up from17% in 1963. The number of people currently living with HIV in Kenya is 2.1 million. The adult rate in the country is close to 14%. The number of deaths due to AIDS in 1999 alone was 180,000 people. We have 730,000 orphans since the beginning of the epidemic. One is considered an orphan after losing one's mother or both parents. The HIV prevalence among sex workers in Nairobi has risen from 62% in 1985 to 80% in 1992.

Now to address some of the factors driving the epidemic. The biggest problem we have is the silence. People are not willing to talk about HIV/AIDS. They are scared of it. Even the doctors are scared of it. Essentially it is because we have an enemy, and we do not have enough answers for it.

The second problem we have is poverty and ignorance. The people who are poor tend to be desperate. They tend to lack the necessary education, therefore they are the ones who are more likely to indulge in risky behavior.

The other problem that we have is mother-to-child transmission. As we are speaking today, despite all the advances that have been made, nothing much is being done about this in our country.

Sadly, I must report (and this is true of Africa), we have a serious lack of leadership and commitment from politicians. You'll find very few governments in our region willing to put aside resources to tackle this problem. You may even be aware that in the recent Africa AIDS meeting in Abuja only about half of the expected heads of state turned up. Let's see how many are going to turn up at UNGASS next week.

Also, some of the cultural beliefs and practices- A lot of emphasis has been put on this, but I just need to emphasize again that the main area of transmission is heterosexual activity, and some of the cultural beliefs and practices such as wife inheritance actually play a minor role.

So, just quickly to run down some of the responses that the Kenyan government has made. One was to establish the National AIDS Control Program, which has been running for the past ten years. I should just mention at this point that the treatment of people living with AIDS is not included as part of the strategies. There has been some procurement of drugs for the treatment of opportunistic infections. This has been done using funds from the WHO and the World Bank. These drugs were purchased from the multinational companies, and therefore, were paid for at prices of the branded products. This was a loan that was given to Kenya to purchase drugs, which were brought in from some of the companies in the US. So the money never left the shores of America.

We have a free TB program in the whole country. All patients with TB are treated for free. This program has been supported for the last ten years by the Dutch government. But as you're aware, there was a recent election in Holland, and they reduced the number of countries they supported from 63 to 15 on the basis of accountability and transparency. Kenya was one of the countries which did not quality. So, out of the bathwater went our TB program. We are now seeking support again from the WHO for a TB program. Again, we have to buy the products from internationally- recognized companies, many of them based in the United States. The money we shall be given will, again, not leave the shores of the United States for the TB program.

We also have universal voluntary testing and counseling centers all over the country. This has been an effort of the government to make testing widely available. We have also had some procurement of treatment for sexually transmitted infections. Again, the drugs used for the STD program have only been bought from branded multinational companies. We have been buying, for example, ciprafloxazin from Baer. The prices tend to be quite high. The funding was able to run the program for two years, and then the funds were exhausted. As we are talking today, the STD program has virtually ground to a halt. As you are well aware, if you manage STDs properly and efficiently, you will be able to cut down transmission between a quarter and a half. Unfortunately, that is one option that we are unable to use at the moment.

One of the statistics we have been able to distribute, as of last year, 22 million condoms, up from 1 million in 1984. It means that the consumption is higher and we hope that this is one of the positive signs of behavior change.

We've also had an aggressive awareness campaign. This is where a lot of money has gone in from different partners. A lot of the prevention money has gone into raising awareness. In the last demographic survey, there was a 98% knowledge rate in the 15-49 year-old age group. That has been quite effective.

We still need to tackle the question of stigma. People living with AIDS are afraid to visit hospitals because the medical staff have a strong bias against them. They will have to wait in line. They will not be touched. They will be spoken at instead of spoken to. So, patients are afraid of the indignity that they will suffer. Most people will only go to the hospital when they have no choice.

I know you've heard a lot about the issue of infrastructure. I would not call our health system "state of the art". It has its own problems. Suffice it to say, we have some problems which we need to deal with, including, not having enough doctors in the first place. Another issue is the drug supply system which is being worked out between the World Bank and the German government. There are some areas which are being looked at, and in fact, there is a lot of improvement so far.

One of our biggest problems is the funding for anti-AIDS activities. A lot of the money comes from foundations and UNAIDS, but you'll find that within the country itself, very few resources are mobilized, which I think is a pity.

Home-based care for people living with AIDS- this I see as the best possible future strategy for our country. Looking after patients at home, asking their family members to give them the love and the care, which they need and deserve, which is better than we can ask for from the hospitals. This is a strategy, which we still need to work on. Groups such as Action AID and MSF are working on this strategy. It is a strategy in which we need to invest more.

Another issue is inadequate drugs, which you have heard about from the other presenters. Another issue is the lack of trained staff to manage some of the more complicated aspects of HIV care. When we talk about antiretroviral drugs, for example, there are some technical skills, which are required. That is an area in which we need to polish up a little bit. Already, our country has come up with guidelines for ARV treatment. We will be starting a course shortly which all medical doctors will have to go through before they can prescribe these drugs.

On the issue of laws- Kenya has recently been able to pass a TRIPS agreement, the industrial property bill. The bill that was initially prepared was TRIPS-plus, in other words, the Kenyan government, with advice from YPO and the WTO, had prepared a bill which actually asked for more than TRIPS required, but with the intervention of MSF and the Kenya Access to Essential Medicines Coalition, we've been able to pass a more friendly intellectual property bill. Now we shall be able to have the legal options of some of the measures that we've already talked about- compulsory licensing, parallel importing. We even managed to insert some of the issues like the ---- exception, which we may be able to talk about later.

We still have the issue of lack of access to antiretroviral drugs due to their cost. Production of bad governance. This is a problem. We cannot deny it. We still need to have political enlightenment in Africa. A lot of the leaders there feel that it is their time to eat, as they call it, and they forget that they are supposed to serve. That's a problem we need to deal with.

So, just to recap, Kenya's a signatory to the WTO, so we were supposed to be compliant by the year 2000. The industrial property bill of 2000, which was drawn up with the assistance of the WTO and YPO, which was TRIPS-plus, was delayed, as you are aware, due to succession politics. The current president in our country is supposed to retire next year. Already, he claims that he still has a few years to go and would like to continue. In the process of dealing with succession politics, the bill was delayed. However, the new bill that the Coalition pushed for 2001, which was quite favorable, was passed two weeks ago.

This is the most important part I think we should address. There are different ways that some of the Third World countries can help each other and themselves. First of all, we are looking at the issue of tiered pricing, where drugs are priced according to the Human Development Index of the country. We have three categories of countries looking at the UNDP classifications. We are asking, if it can be done, for drugs to be sold, and the prices to be varied depending on the Human Development Index. For example, the poorest countries get the lowest prices. I don't know if you'll agree, but maybe the richer countries will pay higher prices and help to subsidize for the poorest people.

There is also the issue of regional procurement, which is already being practiced in the Caribbean countries. The countries come together to purchase in bulk in order to command larger discounts. This does not require any legal procedure. This is something that East African countries could do, for example.

On the issue of voluntary licensing- local companies requesting a license from a larger company to produce drugs without legal hindrance. Some of these licenses have been requested by East African companies, but all have been rejected so far.

On new alternative funding, if we look at the initiative by the Secretary General of the UN, we know that we already have problems with malaria, TB, and sleeping sickness, and these problems will continue. Mother-to-child transmission will also continue. To deal with HIV we need new money. Some of this new money must be raised not only by the UN, but also by the countries which need it.

On the issue of parallel importation- now can be done using the new law that we have passed. We are also addressing compulsory licensing, local manufacturing with the proportion incentives (voluntary licenses plus incentives from the government, such as reduced income tax and free land).

Gifts and donations is another issue we must address, although it is not a long-term solution, it's an option. This has already been done by Pfizer with fluconazole.

Now, I would just like to talk a little bit about what HIV means to us in the field. As you're all aware, most of you when you visit your physician or doctor, the most common problem that takes people to see their doctors is pain. I just want to talk a little bit about one of the diseases that frequently strikes people living with HIV in Kenya. In this instance, I will talk about a fungal meningitis called cryptococcal meningitis. Most of you may have heard about this condition. It kills one in every four people living with HIV in Kenya. We are able to make a diagnosis quite quickly after doing a spinal tap.

About three months ago, a patient came to see me at the clinic, which we run exclusively for HIV patients. He did not know that he was HIV+. In fact, he was referred to me by a colleague. His main history when he came to see me was that he had had a splitting headache for the past fourteen days, and he happened to come with his wife and two children. He was working with our Ministry of Finance in the Treasury Department. Let's call him Simon. So, Simon came into the clinic and told me that he'd had this headache that was getting worse. It's been fourteen days and he's had no relief. He'd been sent to me, so he believed that if another doctor sent him to me, then surely, I had all the answers.

The doctor who had seen him before had done all the necessary tests and had ruled-out other causes of headache that we normally see. I did a spinal tap for Simon in the small side lab in my clinic. The diagnosis was what I feared- cryptococcal meningitis. It is a diagnosis that can be made in two minutes. So, I went back into the room where Simon was sitting with his wife and two children, twin girls. He asked me what the problem was. I told him that he had meningitis. That in itself is quite scary. So, he said, "Do I need to go into the hospital to get treatment?" This is where the difficult part comes. To treat fungal meningitis in Kenya you need fluconazole, and fluconazole has been going for $10 per tablet, and a patient needs two tablets a day for the first fourteen weeks. This is way out of Simon's price range. So, I told him, "No, I cannot admit you because the drug that you require is really expensive." He asked me how expensive and I told him its price in Kenyan shillings. After a quick calculation we discovered that within the first six days of treatment, his salary would be over, and his twin daughters would not be able to go to their kindergarten. So he asked me what the other options were. I told him, "This form of meningitis can only be treated with this one drug, and if you can't afford it, unfortunately, I can't help you. We do not admit patients who have your diagnosis, and I am forced to turn you away." I think that he couldn't believe that this kind of conversation had happened. He then asked what the next best option was. I asked him where his home was, and he told me that he lived 200-300 km outside of Nairobi. As you all know, it is much more expensive to transport a dead body than a live one. So, I told the family that their best option was to go home, so that when he dies, which is normally within fourteen days of diagnosis, he can buried without expensive transportation arrangements.

Having this conversation almost every other day with every patient makes practicing medicine really difficult. Especially when you know that in Thailand, they can make fluconazole for 15 cents. I can't get access to those drugs due to the patent laws. I would be breaking the law. This happens all the time. It's happening in Kenya in many clinics. It's happening in all of Africa o many patients. The twin daughters lost their father, and the mother lost her husband. That is how she discovered that he had HIV.

I think poor countries have the obligation to look after their citizens in the best way possible. The poor have a right not only to their basic human rights, but also to the policies that make these come about. They have a right to be free of HIV/AIDS, and they also have a right to create, through laws, the necessary environment to make this a reality. What we really hope to get out of the UNGASS meeting is for the poor countries to be able to use the means that are necessary to treat their patients without pressure from governments insisting on the proper observation of intellectual property rights at whatever cost. Thank you very much.

Anne-Valerie Kaninda:

You mentioned a donation from Pfizer. Will the situation with Simon cease to occur once the donation of fluconazole has occurred?Chris Ouma:

Unfortunately, Kenya doesn't qualify for the Pfizer donation because we are listed among the developing and not the least developed countries, so we are technically knocked out of that one.Anne-Valerie Kaninda:

So that patent is still enforced on fluconazole in Kenya?Chris Ouma:

That's right, for the next two years.Dr. Chris Ouma graduated from the Nairobi Medical School in Kenya. He has treated HIV+ patients in Nairobi for more than five years. He joined MSF in 1997 and has been running MSF's HIV/AIDS programs in the Nairobi slums for three years. The program provides basic care, palliative care, and treatment of some opportunistic infections. Chris is now working with Action AID, another NGO, and is a strong advocate for treatment for all those who need in Kenya.

Questions from the Audience

following Dying from Lack of Treatment: The International AIDS Crisis, An MSF-sponsored panel discussion, June 21, 2001

Left to right : Moderator Dr. Anne-Valerie Kaninda, Panelists Dr. Konstantin Lezhentsev, Onanong Bunjumnong, Dr. Rose Mougnutou, Dr. Chris Ouma |

How does treatment affect prevention efforts?

Chris:

A lot of governments use the excuse that prices are too high. If people realize that care is available and affordable, then they will have more interest in knowing their HIV status because they will get a benefit. For example, if we had a strong mother-to-child prevention program for HIV, then mothers in the antenatal clinics would be more willing to be tested because they would know that this would help their unborn children. People know that if they get diagnosed with diabetes then they will be able to go and buy insulin. If HIV drugs were available, then people would be more interested in knowing their status and then doing something about it. Therefore, it would be more compelling for governments, knowing that treatment was accessible, to use their resources. Right now they are too happy to say that drugs cost too much and spend the money on something else. I also think that the nurses attitudes would change greatly if they knew treatment was available. This is one of the biggest problems in the hospital where I work. The nurses know that the people coming in will die whether they put in a lot of effort or not. If they knew that their patients could get drugs, walk out of the hospital, and go back to work, I think their attitude would change. It's the availability of treatment that would change a lot of things.Konstantin:

In my country, prevention messages are aimed at changing people's ideology toward avoiding risky behavior. The main obstacle facing prevention efforts is fear. When HIV/AIDS is seen as a death sentence, prevention messages are not effective.Rose:

Antiretroviral treatment has encouraged the families of my patients to get tested themselves. The first question that a patient asks when we offer them testing is, "What am I going to get out of it? If it means that I'm going to die, then I don't want to know." When treatment is available, people are willing to be tested.Are any of the other former Soviet states implementing mother-to-child transmission prevention programs?

Konstantin:

MSF-Ukraine was the first program to implement a mother-to-child transmission prevention program using nevirapin. The project is now developing nationally through government support. A UNICEF program using AZT is also occurring in Ukraine. In Russia, the government is implementing an AZT project as well.How did recent price drops by pharmaceutical companies affect the situation in the field?

Onanong:

I would like to use the example of a CIPLA offer of $600 per patient per year. In Thailand, we have not yet benefited from the CIPLA offer because the Thai FDA has not yet registered the generic drugs. Our FDA has a very high standard and has not approved CIPLA's nevirapin, d4T or 3TC.Chris:

I don't want people to get the wrong impression. We are not against patents or drug companies making profits. What we want is for poorer countries to be able to use legal measures to get drugs. Some of the price cuts which the drug companies have offered are really unprecedented. However, let's remember that these price cuts have only come under pressure, and especially, after the CIPLA offer. You will notice that the price cuts that have been offered tend to mirror very closely those made by generic drug companies. I don't think that these offers are being made entirely in good faith. I think that a large part of them were made to keep the generic companies out of these markets. However, I must concede that in Nairobi now, drug prices have come down quite considerably for some. For example, the price of nevirapin has come down by about 85%. The prices of some of the other Glaxo products, for example, combivir, have come down by about 25-50%. So, there has been a real price reduction. However, as long as governments have the power to get the drugs from alternative sources if they feel that the market prices offered by these companies is not satisfactory, they will be able to keep some sanity in the pharmaceutical markets and keep prices affordable. We have had some movement generated by the CIPLA offer, but we must insist on our right to buy drugs from other sources if we feel that the prices being quoted by the branded companies are not the best that we can get.Konstantin:

We intend to strongly advocate the purchase of CIPLA's generic drugs by the Ukrainian government. We are completely unsatisfied with the current price of $9,500 per patient for drugs in the year 2000. That price was offered only after three years of negotiations and big announcements from Glaxo Smith-Kline (which was then Glaxo Wellcom) about an 80% price decrease for Combivir. It was also after the Boehringer- Ingelheim announcement in Durban that they would provide neveripin for free to prevent mother-to-child transmission. A year later, B-I is still selling this drug to the regional authorities. Finally, a few months ago, after stimulation from activists, Mr. Boehringer himself came to Ukraine to announce that they will donate neveripin for four years. Of course, this will be done only after the system capacity is increased and doctors are more informed, etc.Rose:

The arrival of generic drugs on the market has greatly changed the outlook for patients in Cameroon. Previously, antiretroviral drugs cost $300 per person per month. Now they cost $100, which although still expensive, is an improvement.What do you expect from UNGASS?

Chris:

From our perspective, we hope to see three particular areas of improvement. The first, is to increased pressure on the political leadership of Africa, especially sub-Saharan Africa. Secondly, we would like to see a dual system in terms of intellectual property rights where the rich and the poor can both be satisfied. The third area we are looking at is resources. We do not want to take money away from services that are already being provided, but need to raise new money. We need to see more stress on the care component. Prevention is the most cost- effective strategy, but there are too many sick people for us to focus only on prevention and not on care. We want to see prevention and care at the same time.Please comment on the issue of HIV/AIDS as it relates to women's empowerment.

Konstantin:

The epidemic in my country is shifting from transmission mainly through intravenous drug use toward transmission through heterosexual sex and mother-to-child transmission. The gender question is now coming more to light. Programs aimed at women from the most vulnerable group (commercial sex workers) have been sponsored by international donor organizations and the government. These programs focus on education and condom distribution.Onanong:

Thailand has been successfully at implementing 100% condom use a few years ago. These programs focused on commercial sex workers and intravenous drug users. Now, as the prevalence of HIV/AIDS rises among other groups, education programs must expand as well.Rose:

Cameroon is not only faced with the problem of condom use, but also that of polygamy. One man can therefore infect many wives. We are trying to educate young women to help prevent the problem from spreading.Chris:

About three months ago, there was a National Women's Caucus meeting in Kenya. The President was invited to open the meeting. After reading his official speech on national television, he made and off-the-cuff comment which has gained national infamy. He said, "You women could have achieved a lot, but because of your small minds, you still have a long way to go." Needless to say, on the issue of gender, we still have a way to go. However, it is has been left mainly to the NGOs to deal with. There are many cobwebs in our political leadership that must be dealt with. This is a complex issue. Politics plays a large part in it, and we must get that kind of thinking out of the government if we are going to make progress on this issue.Will the new law signed in Kenya allow the country to have access to generic fluconazole within the next few months?

Chris:

The law was passed two weeks ago. This is one of our priorities, but we haven't discussed it with the government yet. When it comes to access to essential drugs, fluconazole is our highest priority at the moment because we can monitor its effects, diagnose it easily. Nevirapin to prevent mother-to-child transmission is our next highest priority. We want to import fluconazole from Thailand because they have given the most attractive offer. According to the legal definition of parallel importation, we should import Pfizer products from a country that has legally put them on the market. We still do not know how it applies to the purchase of generic drugs from another country.What is your position on bio-equivalency standardization and testing?

Daniel Berman (Coordinator, MSF's Access to Essential Medicines Campaign):

The WHO is undergoing a process that they call "pre-qualification". They've put out requests to suppliers of drugs for opportunistic infections and antiretrovirals. In the next couple of months, the WHO is starting to pre-qualify them, stating that they meet their standards. This would allow generic drugs to be on equal footing so each authority in the developing countries would not have to go through that process individually. The results of the first wave of products should be available by the end of the year.Do you believe that lowering prices will negatively affect the research and development of drugs in the future?

Daniel:

We've been examining the difference between the research and development needs of developed vs. developing countries. If you look at the revenue within wealthy countries, you will see that there is no lack of stimulation for research. We are not in any way against patents. The issue is that the actual cost of production of drugs is very small compared to the price. The lion share of the cost is for research and development. On the other hand, there is a real crisis in research and development for neglected diseases such as malaria, TB, and sleeping sickness because these drugs don't have a viable market from a drug company's perspective. For those diseases, we believe that there need to be other solutions such as public-private partnerships or non-profit entities.Anne-Valerie Kaninda:

MSF strongly believes that it is a government's responsibility to ensure that its citizens have adequate access to medical care. There has been a lot of media pressure recently on pharmaceutical companies, but these companies are not in charge of global public health. The primary responsibility lies with governments. The UNGASS session next week should reflect that fact. Global policies are needed to ensure that people have access to the drugs that they need.Dr. Chris Ouma graduated from the Nairobi Medical School in Kenya. He has treated HIV+ patients in Nairobi for more than five years. He joined MSF in 1997 and has been running MSF's HIV/AIDS programs in the Nairobi slums for three years. The program provides basic care, palliative care, and treatment of some opportunistic infections. Chris is now working with Action AID, another NGO, and is a strong advocate for treatment for all those who need in Kenya.

|

Good evening, ladies and gentleman. Thank you for coming tonight. My name is Anne-Valerie Kaninda. I am the Medical Advisor for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières in New York. As you know, more than 34 million people are infected with HIV. 95% of those infected live in the developing world and do not have access to adequate treatment, to effective treatment of opportunistic infections, or antiretroviral therapy, even though these treatments are available. 8,000 people die from AIDS every single day. Meanwhile, the international community is telling AIDS patients in the developing world, "I'm sorry, you will die because treating you is not cost-effective." For us physicians, this is shocking. It is contrary to the most basic medical ethics. We do not agree to simply write off 34 million people's lives when we know that treatments exist. Tonight we have four people working in our field projects in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. They are all fighting to provide adequate care and treatment to people living with HIV/AIDS. They are going to share with us their experience.

Antiretroviral Treatment in Ukraine: The Bitter Pill

[Read]

Konstantin Lezhentsev, M.D., MSF-Ukraine, is an advocate for affordable AIDS treatments in the Ukraine where he works on MSF's HIV treatment program for mothers and their children.

Access to Affordable AIDS Medicines in Thailand

[Read]

Onanong Bunjumnong, MSF-Thailand, leads MSF's Access to Essential Medicines Campaign in Thailand, where MSF has been treating people with AIDS for 6 years.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS by ARVs: The Experience of Cameroon

[Read]

Rose Mougnutou, M.D., MSF-Cameroon, has been treating people with AIDS with anitretrovirals at the University Hospital of Yaounde for over 3 years. She currently works in an MSF pilot project providing antiretroviral therapy.

Treating HIV/AIDS in Kenya

[Read]

Chris Ouma, M.D., Action Aid Kenya, treats people with AIDS in the slums of Nairobi and has been an outspoken critic of international trade agreements that have kept antiretrovirals out of the reach of his patients.

Questions from the Audience

[Read]

Good evening, dear friends. My name is Konstantin. I'm a medical doctor working in an MSF-Holland project in Ukraine. I myself am one of this country's 50 million citizens. Ukraine is now known in Eastern Europe as an epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The AIDS epidemic in the Ukraine is developing from a few cases in 1987 into a full-blown epidemic that has touched all-levels of Ukrainian society, including the most productive… our youth.

At present, as of April 2001, according to the official statistics, there are 38,109 people infected with HIV AIDS in Ukraine. These official figures account for those whose diagnosis was confirmed by double testing. However, the UNAIDS experts estimate that there are more than 300,000 people living with HIV in Ukraine. By the year 2014, they estimate that there will be 1.5 million people infected with HIV. The experts estimate that the cumulative death toll from AIDS is 9,400 people.

The epidemic first affected a marginalized group of Ukrainian society—intravenous drug users. Around 60-80% of HIV+ people were infected through IV drug use. Although injection drug users still form the majority of people infected with HIV, the epidemic has reached a new phase. There is now substantial growth in both heterosexual and mother-to-child transmission rates. The majority of HIV+ people in Ukraine are under 30 years old.

Despite the fact that Ukraine officially recognized the HIV/AIDS situation as an epidemic, that the State Committee on HIV/AIDS was formed, that since 1995 major donor international organizations started a bunch of programs concentrated on prevention only, adequate medical care including ARV treatment, effective treatment and prevention of opportunistic infections, palliative care, and modern methods of diagnostics are not available for people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine.

Despite the fact that major pharmaceutical representatives in Ukraine are constantly expressing their desire to decrease the price of ARV drugs (antiretroviral drugs) and to start fruitful negotiations with the Ukrainian government about the price decrease, there has been no actual decrease. The lowest price offered by the government for the year 2001 was $ 9,500 per patient per year for combinations of Nelthinavir-Combivir, Indinavir-Combivir, or Nevirapin-d4T-ddI, the combination that has been successfully improving the quality of life for patients living with HIV in the developing world. The health care budget for the year 2000 for all HIV programs including prevention programs was $ 2.2 million. The amount of funds allocated for treatment was $164,000 for adults and $180,000 for children.

These figures underline the crucial need for immediate implementation of all existing mechanisms for a price decrease to make HIV/AIDS treatment available for all those who need it in Ukraine.

Ukraine was the first country in Eastern Europe to officially recognized its responsibilities in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Ukraine was one of the countries that initiated the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on HIV/AIDS. Our closest neighbors from Eastern Europe, such as Poland, are providing treatment for their HIV+ citizens. International agencies assessing the pharmaceutical capacity of Ukraine describe Ukraine as a country of generics, reflecting the high production and importation of generic drugs such as antibiotics and antifungal drugs. Ukraine should not be permitted to get stuck in the continuous circle of excuses given by pharmaceutical companies and some international agencies. It is obvious from the experience of other countries that a number of excuses for not providing treatment are always available. They are: Build an infrastructure and system capacity first. Poor compliance from marginalized HIV+ individuals. (That means discrimination of intravenous drug users and homeless people). Prevention should be the mainstream of an effective response. These are the standard phrases that are used on the global and regional levels, but what that really means is that HIV+ people will die.

People living with HIV in Ukraine cannot wait for all these negotiations to take place in standard process. They do not have time for this, and I, as a member of MSF, and as a Ukrainian citizen, cannot allow these people to die on the side of the road of a wide range of prevention interventions.

The hopes of my colleagues and partners, people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine, people helping others to overcome the social, psychological, and economic problems associated with HIV/ AIDS and dying from the lack of treatment in Ukraine, cannot be eclipsed by general phrases of "examining alternatives for increasing access and affordability of HIV/AIDS related drugs." The possibilities should not be examined, but implemented immediately in all countries where treatment is not affordable for those who need it. The main obstacle for making treatment available is the concern that treatment is not possible. Treatment significantly improves the quality of life of those living with HIV in the developing countries. There is no excuse for not providing it due to economic reasons.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS is feasible and the cornerstone of effective prevention. Moreover, the development of the HIV epidemic in Western countries was effectively prevented only when treatment was implemented for HIV+ people. Until the stereotype of an HIV diagnosis as a death sentence changes, there is no way that preventative messages will be effectively accepted by the general public and effective change in risky behavior will occur.

Poor infrastructure and compliance from patients should not be an excuse for the pharmaceutical companies and the governments for not making treatment affordable. A more appropriate response would be overcoming the obstacles to a good infrastructure by involving the NGO sector and not permitting the discrimination of certain, marginalized groups of patients such as HIV-positive drug-users and homeless people.

From the very beginning of the development of the MSF project on preventing mother-to-child transmission in Ukraine we have been working hand-in-hand with people living with HIV/AIDS. These people became our close partners, professional and motivated. The experience of our collaboration showed that they are the real force that can effectively defend their human rights (first of all the right for adequate medical care), that is able to fill the infrastructure gaps and provide compliance of patients for treatment and be a relevant partner for the government on all levels in revising existing strategies in order to increase their effectiveness.

I want to share with you my honor and respect for these people, their courage and willingness to help others. I want to honor those Ukrainian doctors who do their best to overcome poverty, absence of information and discriminating attitudes towards people with HIV and who provide adequate help to their patients.

Natasha.

I want her to be able to help others as she does now.Dima.

My colleague. I want him to be able to give adequate treatment to his patients.Alya.

My friend and colleague. I want her to stay with us.Natasha.

My friend and colleague. I want her to see her son growing.Sergei.

My friend and colleague. I want all of his dreams to come true.Ivanka...

During my first exploratory mission with MSF two years ago she was born. I was so excited to be a part of a powerful international organization that I looked at her and was very optimistic about her future, about confirmation of her HIV- negative status, about her life … Ivanka died at the age of two years. She was born HIV-positive just a few months before MSF's project on prevention of mother to child transmission had been started in her region. She was not a rapid progressor of HIV-infection, but she had strong indications for starting ARV-therapy.My patients and my colleagues are tired of continuing negotiations, of nice smiles of healthy patients from the pharmaceutical commercial posters hanging on the walls of the hospitals where people die from lack of medicines, of expired drugs given as a "charity humanitarian donations" from pharmaceutical companies.

There is no excuse for not providing treatment to people, the treatment is feasible and is a right of every human being regardless of his or her social and economical status.

As a medical doctor and MSF member, as a citizen of Ukraine, I can confirm that until the treatment will be provided for all people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine, until the term "death sentence" is no longer associated with HIV infection, all the huge efforts of the main international organizations focusing on prevention will not be effective.

Treatment is a cornerstone of prevention, the crucial aspect in changing ideological stereotypes toward HIV in society and thus the real "cost-effectiveness" of combating the HIV/AIDS epidemic in my country and worldwide.

Question:

How are people living with HIV in the Ukraine organized?During the past year, crucial steps were made in their organization. Many are now a part of the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS. The network was created at the same time as the AIDS epidemic was given political recognition in the Ukraine. They set up self-support groups and fill in the gap of the infrastructure. Representatives of the Network are part of the official delegation of Ukraine to the UNGASS on HIV/AIDS. This delegation includes the Vice Premier Minister of Ukraine and the Minister of Health.

Question:

What is the situation in the other former Soviet Republics, and how does it compare with the Ukraine?The Ukraine is the epicenter of the epidemic. 1% of the population is infected. In Russia, there is also rapid progression. Itravenous drug use is the main route of transmission. The Baltic Republics have fewer cases. Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan are now only developing their statistics. Countries such as Bella Russia have far fewer cases than Ukraine or Russia.

Question:

What is the average age of intravenous drug users in Ukraine?Under 30 years old.

Access to Affordable AIDS Medicines in Thailand

Delivered June 21, 2001 by Onanong Bunjumnong as part of the MSF-sponsored panel discussion Dying from Lack of Treatment: The International AIDS Crisis.

First I want to thank everyone for coming tonight. My talk will be about access to affordable AIDS medicines in Thailand. I will divide my talk into two parts. The first will focus on the pricing barrier while the second will address patent issues.

In Thailand, it is estimated that one million people are living with HIV/AIDS. The total population of the country is 62 million. Only 5% of every 100,000 people living with HIV in Thailand have access to affordable medicines or antiretroviral treatments. One of the reasons that people in Thailand and other developing countries continue to die of AIDS is due to the fact that they cannot afford antiretrovirals or other essential medicines.

People with AIDS in Thailand can access antiretroviral treatments from the following sources:

- The first way to get ARVs is to buy them at the market price. The following is an example of the cost of triple therapy, the standard combination of antiretroviral treatments. If one bought d4T from Bristol-Myers Squibb, 3TC from Glaxo SmithKline, and neverapin from Burinko, it would cost $15/day. A monthly supply would cost $450. The minimum wage in Thailand is $2.60/day and $80/month. It is impossible for Thai people to pay for their own medicine. Even if they borrowed money from family and friends, they would have to do so for the rest of their lives.

- The second way to access antiretroviral treatment is through a government subsidy. AZT and ddI are subsidized since they are on the Essential Drug list in Thailand. The third drug in triple therapy would have to be paid for from one's own pocket.

- The third way to access ARVs is through clinical trials. There are several clinical trials currently running in Thailand. The first is through HIVNAT (HIV- Netherlands-Australia-Thailand), which covers 1,000 people. Hospitals and hospices run trials that cover 200-300 people.

- The fourth way to access ARVs is through the CDC (Communicable Disease Control) of the Thai Ministry of Health, which covers 3,000 people.

- The final way to access ARVs is through two MSF ARV projects in Thailand that cover 70 people.

Only 5,000 out of 100,000 living with HIV have access to ARVs in Thailand. Only 300 can afford to pay for their own medicines.

The following are a few quotes on this issue. The first is from a woman now in MSF's ARV program who went blind from her HIV infection. She said, "If I could have afforded to pay for my antiretroviral treatment three years ago, my health and my life would be much better, and I would be able to see."

The next is from an AIDS activist. He said, "If I could have afforded to pay for my antiretroviral treatment, my husband would still be alive today."

It is really tragic because we know that treatment exists, but people cannot get access to it because of its high expense.

In Thailand, we rely on generic drugs. In 1998, Pfizer sold fluconazole (a drug for cryptoccocal meningitis, an opportunistic infection) for $6 per capsule. The price of generic fluconazole is only 15 cents per capsule, however.

In July 1992, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) obtained a patent on ddI, one of the antiretroviral drugs commonly used in triple therapy, to maintain a monopoly on the drug. The Thai Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO) was unsure of ddI's patent status, due to the complicated process of the Thai Intellectual Property Department. The GPO researched ddI formulation for twelve years. In February 1998, the GPO planned to launch generic production of ddI. Six BMS representatives flew to Thailand and stopped them in their tracks.

In November 1999, the GPO asked the Ministry of Health to issue a compulsory license for the generic production of ddI under the Thai patent law. A compulsory license is a license for generic production without the permission of the patent holder. The Thai government did not respond to the request.

In December 1999, 68 NGOs and 100 people living with HIV demonstrated in front of the Ministry of Health. They supported the GPO and asked the government to issue a compulsory license for generic production of ddI. After days and nights demonstration, the Ministry of Health agreed to allow the generic production of ddI, but only in powder form, since the tablet was patented.

We know that the reason the Thai government would not allow generic production of the tablet because it was afraid of United States trade sanctions.

One month later, the NGOS and the Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS demonstrated in front of the U.S. Embassy. They requested a clear statement from the U.S. President ensuring that the U.S. would not take any punitive action against the Thai government if they issued a compulsory license. A proposed letter, signed by the Chairman of the Network, was sent to the U.S. President.

Ten days later, the U.S. trade representative responded with a letter stating that the U.S. would not object to a compulsory license to help the Thai healthcare crisis. Finally, Thailand had a green light to issue a compulsory license for the generic production of ddI, but the government still refused to do anything.

At this point, activists and people living with HIV were extremely frustrated. In order to take the powder version of ddI, one had to mix it with water. This often disclosed one's confidentiality because others recognized the powder as AIDS medication. People living with HIV in Thailand are highly stigmatized. Having one's status disclosed only leads to discrimination.

The NGOs, people living with HIV, pharmacies, technical experts, lawyers, and doctors, believe that since the research and development of ddI itself was done by the U.S. Institute of Health, BMS had no right to obtain a patent in the first place. The NGOs and people living with HIV filed a lawsuit against BMS. They feel that the intellectual property laws are unfair to developing countries. A complaint was filed by the Thai court on May 11, 2001. A copy of the complaint was also sent to a BMS representative in Thailand. We are now waiting for their response.

I am standing here today as a representative of an international humanitarian organization and as a Thai citizen. I strongly believe that antiretroviral treatment is feasible and possible in Thailand. I also believe that prices of anti-AIDS medicines must fall to affordable levels and safeguards within TRIPS agreement (which include compulsory licenses) must be practically and effectively implemented. I also believe that political will is desperately needed to overcome treatment barriers for the poor.

Onanong Bunjumnong holds a Masters Degree in Health Sciences. She joined MSF in Bangkok in January 2000 where she first worked as an assistant to the antiretroviral project that MSF started there. The goal of the MSF HIV program in Thailand is to improve healthcare for people living with HIV/AIDS in central Bangkok and in three surrounding districts. It includes several components, among them a pilot antiretroviral project and a lobbying campaign with national activist groups and NGOs focusing on the price of essential medicines for people living with HIV/AIDS. Onanong is now a Communications Officer, specifically focusing on access to antiretroviral treatment.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS by ARVs:

The Experience of Cameroon

Delivered June 21, 2001 by Rose Mougnutou, M.D., as part of the MSF-sponsored panel discussion Dying from Lack of Treatment: The International AIDS Crisis.

Rose works in an MSF pilot project in Cameroon providing antiretroviral therapy to HIV/AIDS patients.

My presentation will consist of three parts. The first is an overview of the HIV/AIDS situation in Cameroon. The second deals with my experience treating HIV+ patients in Cameroon. The last deals with the conclusions I have drawn from my experience.

Cameroon is a country located in Central Africa at the equatorial level. Out of fifteen million inhabitants, almost one million people in Cameroon are HIV+. This represents 11% of the sexually active population.

Here is an overview of the AIDS statistics on Cameroon.

- 937,000 people are living with HIV.

- 52,000 people died from the disease in 1999.

- 91,000 children were orphaned due to AIDS in 2000.

- 5,168 new cases of HIV were transmitted in 2000.

- 90% of them were sexually transmitted.

- 10% were caused by mother-to-child transmission.

- 5,000 children are living with HIV in 2000.

This graph illustrates the evolution of prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the sexually active population from 1987 to 2000:

Here we can see the prevalence by age groups: the most affected group is the 15-25 group nevertheless, all age groups are affected.

The PRESICA project (Prevention of AIDS in Cameroon) is a collaboration between the Public Health and Defense ministries of Cameroon. It is financed by the Research Institute for Development (France), the European Union, and The National Research Agency for AIDS (France). It has enabled the management of a cohort of nearly 400 patients who now have access to voluntary screening, treatment and prevention of opportunistic and non-opportunistic infections, and psycho-social follow-up.

From these 400 patients, the PARVY project selects people for ARV treatment.

The PARVY project (The Antiretroviral Project of Yaoundé) is a collaboration between PRESICA and MSF Switzerland. It started in January 2001. Its objective was to lower the morbidity and mortality rate amongst PRESICA HIV/AIDS patients by providing a specific ARV treatment at no charge. To this day, among the 150 patients who will be included in the next 2 years, 17 are on ARV with a clinical and biological (VL CD4) follow-up as well as therapeutic surveillance. The treatment is sponsored by the project and provided by 6 doctors who specialize in HIV/AIDS.

The PARVY project has been functioning now for 6 months and with only 17 patients it is currently too soon to do statistical evaluations on the benefits of ARV on these patients. To our clinical eyes we can say without fear and unequivocally that the lives of our patients have improved in the past 6 months.

We have noted that there is decrease and almost disappearance in opportunistic and non-opportunistic infections in these patients. There is also a marked increase in appetite and a rapid and considerable weight gain (with a average of 3-5 kilos - 6.6 - 11 lbs. per week).

Here I would like to mention the particular case of a 30 year-old military patient abandoned by his siblings due to his illness which had completely debilitated him to the point of immobilization. He regained 15 kilos (33 lb) during his first month of treatment on ARVs. He now has regained his autonomy and mobility. Today he comes to his consultations as an outpatient.

Generally, most of our patients have a renewed will to live to take on professional activities again since they have reacquired their independence and are no longer a burden on their families.

Nevertheless, even in this short period of 6 months, we have identified problems. They are:

- The rigorous treatment criteria excluded some of the patients that would have wanted to benefit from the PARVY program. This brought the management team to lighten certain conditions of inclusion to the project such as financial factors as well as geographic distance of the patient's home.