The Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) is caught in a terrible downward spiral of destruction. Since 1996, following decades of dictatorship, the country has been plunged into a brutal war. Situated in central Africa, this country shares borders with nine countries, several of which are involved in conflicts in Congo. Foreign armies and Congolese armed groups are struggling for power, siphoning off much of the country's vast natural wealth in the process. Caught in the middle are the Congolese civilians. Threatened by injury and death, and exposed to diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis, and malaria, the Congolese people have few resources to fall back on.

After decades of government neglect and war, the health system of the Congo is in tatters. Congo's 53 million inhabitants face regular outbreaks of meningitis, cholera, measles, malaria, as well as the accelerating spread of sleeping sickness, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS. There are an estimated 2.5 million Congolese displaced inside the country, many of them outside the reach of aid workers. Hospitals and medical equipment are scarce, and many rural communities are totally without health care. Devoted Congolese health workers are doing their best, but they are overwhelmed by the magnitude of the public health problems. The consequences to the people are devastating: There are approximately 25,000 people per Congolese doctor. One in four children will die before reaching the age of five. Less than half of the population has access to clean drinking water. Life expectancy is only 45 years.

A Logistical Nightmare: Providing Aid in a Climate of Insecurity

Providing emergency care to the Congolese people is fraught with complications and danger. Vast parts of this enormous country (almost a quarter the size of the United States) are virtually inaccessible to humanitarian aid. This enormous country has health zones which are larger than some European countries so it requires many resources and sophisticated logistics to reach the people most in need. Transportation between villages can take weeks. Frontlines crisscross the territory and humanitarian aid workers run the risk of being caught in the violence. Despite these hurdles, MSF is providing medical and nutritional care to hundreds of thousands of Congolese citizens in several provinces, on all sides of the conflict.

MSF in Congo: An Overview

Active in Congo since 1985, MSF provides medical relief in several provinces, working in government-held areas as well as territory controlled by rebels. Teams work side by side with Congolese health professionals, in a climate of urgency and insecurity.

The cornerstone of MSF's work in Congo remains district health care in several provinces. MSF aids the health structures that make up a health zone—usually a reference hospital and the clinics and health posts that feed into it, covering about 100,000 people. Activities include supplying medicine, supervising and training health staff, administrating vaccinations and prenatal care, carrying out epidemiological surveillance, and improving water and sanitation practices and facilities. In its district health projects, our volunteers work to treat and prevent the spread of a variety of diseases.

Massive displacement has led to severe malnutrition among the displaced children under five. To address this problem, MSF set up feeding centers throughout the country. In feeding centers in Kisangani, MSF has provided over 10,000 children with intensive nutritional care. Other feeding centers opened more recently in Kitshanga and Basankusu have treated thousands more malnourished children.

Volunteer Accounts from MSF Programs

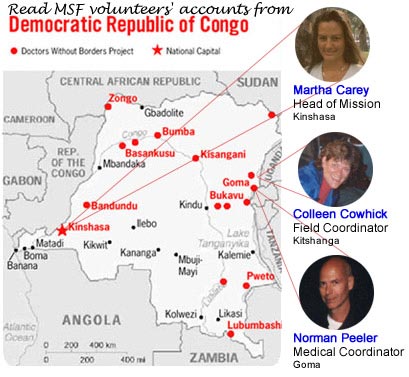

Martha Carey, Head of Mission, Kinshasa, Bas-Congo Province

"When we sent an exploratory team from Kinshasa, the country's capital, to a remote area in Katanga Province, they found cholera. Someone who came to visit the chief—his brother—had brought the cholera. The night he arrived, the village had a big meal together and then the brother became very ill with diarrhea and vomiting. By morning, he was dead. As is done in local tradition, they had a big funeral, washed the body together, and buried the body. Everybody who was at the funeral was dead the next day.

"Before we arrived, there were three functioning health posts in the area. By functioning, I mean that they have a few staff and a building. There are no drugs; there is no medical equipment. Many facilities don't have windows or doors but there are staff accepting people into the clinic and doing their best.

"The death rate was 98% before we arrived. A very large problem was that all the water in this area comes from the river. Also, all the toilets drain into the river. So once you have a village that is attacked with cholera, the cholera is going to follow to other villages downstream. Village after village was affected. As soon as one person fell ill, the rest of the village would flee into the bush trying to look for alternative water sources and to get away from the contamination.

"Our logistical team started very, very quickly. They went to every village and spoke to the chiefs and explained cholera to them—how to prevent it and disinfect the village. This meant going into every home and spraying with chlorine. As the disease continued to move downstream, our biggest fear was that it would enter the Congo River. So our team was very active conducting health education, talking to chiefs and health care workers, training people in the villages, moving patients, and providing chlorine. After about two and a half weeks, the cholera was almost gone."

Colleen Cowhick, Field Coordinator, Kitshanga, North Kivu

"Bordering Rwanda and Uganda, the North Kivu area is extremely fertile and the vast majority of the people are farmers. However, since the advent of the wars, thousands of people have had to flee their homes, crops have been pillaged, vehicles are at risk of attack, and an unknown number of thousands—perhaps millions—of people have been killed or have died from various, usually treatable, diseases.

"My first impressions of the village where I was stationed were of profound poverty, zero infrastructure, and the intense shock at the condition of the children. It's hard to see severely ill children; I was quick to cry and even had to fight being physically ill. The ages of the children ranged from six months to 10 years old.

"Often, we had to start children on direct feeding through stomach tubes because they were so weak. They couldn't even sit up to eat. We also used intravenous feeding, gradually building them up to solid foods. Due to the large volume of children, we had to bring the center up to speed quickly.

"We occasionally saw war wounds—people that had been slashed to ribbons with machetes or who had been shot. It wasn't unusual to hear gunfire in the distance.

"Security was a huge issue. There were constant battles breaking out all around us. We actually evacuated and shut down our project twice, not knowing if we would be able to go back. Luckily, in both instances, we were able to return. There's this constant edge to life there, and you never know when something's going to happen."

Colleen also tells us:

"In early August 2001, a 12 year-old girl made her way on foot to our center with her year-old brother. He was admitted very weak and ill. In January, rebels had come to her small village demanding food. When the rebels were dissatisfied with what the village gave, they attacked the village, killing residents and burning homes. Her four older brothers, mother, and father were all killed in her presence. She was raped and told to stay in the house as the group proceeded to torch the surrounding houses. Naked, she grabbed her baby brother and fled into the bush.

"With every member of her immediate family dead, she set out on foot to find an aunt in a distant town. It took her five months to get there but she successfully found the aunt and was taken in. Upon arriving at her aunt's home, she learned of the MSF feeding center, and eventually made her way to us.

"She told this story in an even tone and with a blank face, but the trauma was clear. Tears streamed down her cheeks. It is unclear how she kept herself alive, let alone a baby. But after some time at the feeding center, she and her brother both improved in health and were discharged."

Norman Peeler, MD, Medical Coordinator, Goma, North Kivu Province

"The nature of the war in Congo is small attacks on villages, for whatever reason, whether it is ethnic, political, or just random violence. The civilians flee into the jungle, where they may stay for a few days or they may go to another part of the Congo—to another town that might be a week away—or they may just hide out in the jungle and come back in a month or two. During wartime, everything gets compromised. You have a complete breakdown in the normal support systems. You have no health care, and your means of survival are diminished. The Congolese people are on the edge all the time.

"People die in the jungle from absence of proper shelter, disease, and poor nutrition. They get malaria, measles, and pneumonia—but they have absolutely no access to health care. From August 1998 to April 2001, there were 2.5 million people killed in the war in the eastern Congo. That's extraordinary. Approximately 14 percent or 350,000 of these deaths were directly a result of violence."

Since 1985, MSF has assisted nearly 30 health zones throughout Congo. Currently MSF employs 80 international volunteers and 730 national staff in DRC.